Nandi is a Junior English Major and a student staff member in the Women’s Center.

Content Note: This blog is written from an African-American woman’s experience and somewhat limited knowledge of the subject.

Hoodoo is an African American folk magic tradition that is based in West African religious beliefs and practices. Much of the history of the practice has been documented through oral histories transcribed by Black historians.

Zora Neale Hurston’s article, “Hoodoo in America” (1931) recounted what she learned on a months long anthropological journey in New Orleans, which was one of the first of its kind. To stay in contact with the deities, traditions, and Africanisms that the slave trade and colonialism worked hard to systematically erase, slaves from West Africa merged a great deal of their traditions and mixed them in with the Christianity taught to them by their captors.

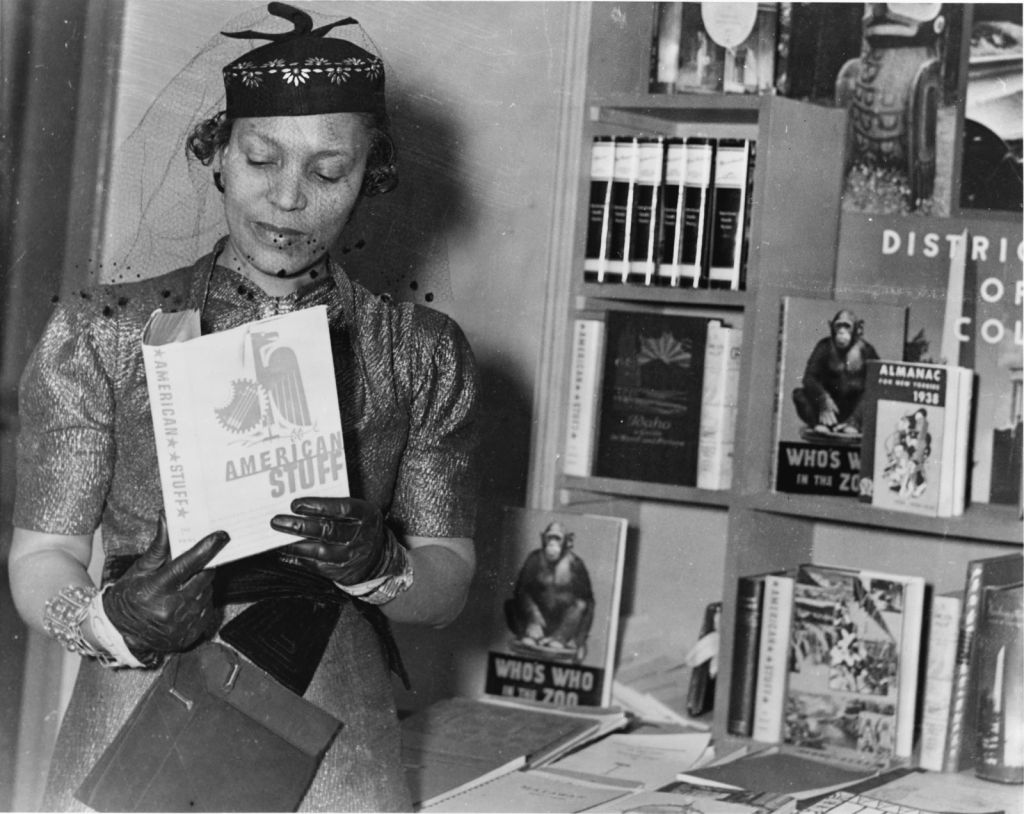

Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Neale Hurston

Practitioners are called Hoodoos, spells are called roots (pronounced ruht), and the strength of the root is in the mojo of the hoodoo. Those who were born directly into the craft, like the famed Marie Laveau of New Orleans, are known to have the strongest mojo. Mojo, or interchangeably, juju, runs through families like a particular nose shape might. Those African-American communities that are more isolated, like the Gullah/Geechee people of South Carolina, are better able to pass on mojo and conjure traditions.

Hoodoo Spell Jars

Hoodoo Spell Jars

In our community, intergenerational wealth is hard to come by, so the practices that get passed down through time act as a different sort of currency to support us through life. Knowledge of, and connections to, ancestors and folkloric spirits form a safety net of divinity that stretches everywhere that Black heads lay down to rest. The guardians and preservers of this wealth are mostly women, of course. Hoodoo and mojo aren’t restricted by gender in any way, but across cultures women are diligent stewards that pass down traditions as part of their assigned roles as caretakers.

The designation of “witchcraft” and the social, legal troubles that go along with practicing religions outside of Christianity (and really just the Christianity du jour) have consistently plagued non-men due to the compounding nature of Eurocentric prejudices. In short, we are seen as evil and scapegoated anyway, so to focus on us in this particular form of deviance is just the path of least resistance. But this is part burden, part responsibility, part honor because being the keepers of the keys to rituals that can harm, heal, protect, and cleanse is a more powerful position to hold than colonizing forces could ever fathom.

Witch-burning in the county Reinstein (Regenstein, Saxony-Anhalt, Germany) in 1555. Woodcut engraving after an original of a leaflet in the Collections of the Germanisches Nationalmusem in Nuremberg, published in 1881.

Witch-burning in the county Reinstein (Regenstein, Saxony-Anhalt, Germany) in 1555. Woodcut engraving after an original of a leaflet in the Collections of the Germanisches Nationalmusem in Nuremberg, published in 1881.

I decided to get into Hoodoo because of the mystic, spiritual motifs that have been ever-present in my family life. My mother and my aunties spitting on brooms, throwing salt over shoulders, never placing bags on the floor, and having premonition dreams seeped into my brain to make me want to go back to the source. The superstitions, belief in luck and omens, that I used to take for granted are everyday expressions of culture and our connections to a divine presence.

I decided on Hoodoo because my family is from the Carolinas, by way of slavery, and that’s where it was developed. The religion was created by and for displaced Africans and their descendents in the Americas. To practice Hoodoo without having any such connection is extremely inadvisable (play with slave spirits if you want to, but you probably won’t like the results