Alexia Petasis is a student staff member at the Women’s Center. Alexia is pursuing an individualized studies degree with a concentration on social justice and dance. She is a co-facilitator for Pop-Culture Pop-Ups.

Alexia Petasis is a student staff member at the Women’s Center. Alexia is pursuing an individualized studies degree with a concentration on social justice and dance. She is a co-facilitator for Pop-Culture Pop-Ups.

This past year, I went to see the San Francisco Ballet at the Kennedy Center for the premiere of new works from various choreographers in the nation. The show consisted of around eight separate dances; some solos, duets, and quartets. The dancers held my attention throughout the lengthy, three-program show as they moved with strength and elegance.

However, I quickly noticed the lack of racial/ethnic diversity on the stage. Under-representation is not a recent problem in the realm of classical or even contemporary ballet. This issue dates back to the 17th century when ballet first became popularized in the courts of European nobility and was, as one can imagine, plagued with discrimination and racism. Unfortunately, the whiteness that engulfed ballet back in those days still exists today, around 400 years later.

Admittedly, I can only speak about this issue from a privileged perspective. I always loved the style of ballet, but I question if my love for it is also correlated in part because I saw others who looked like me doing it. Even from the beginning of my dance training when I was 7 years old, I never believed ballet was an unattainable style of dance for me. The standard attire that is worn for ballet class are pink tights and pink ballet slippers; and though no one has “pink” skin, it is meant to represent closely the skin of white folks, once again perpetuating the notion that people of color are not even considered within this art form. (Significantly, while writing this blog, the New York Times released an article stating that Freed of London released new pointe shoes for black, Asian, and mixed raced dancers.)

Misty Copeland garnered the attention of the media and the dance community by being the first African-American woman to become a principal dancer (one who dances at the highest rank) for the American Ballet Theatre. Yet, the fact that she is still the only African-American woman in the nation to hold a principal role sheds light on the issue of the overwhelmingly large number of white ballet dancers and how they are given priority within this community. Nonetheless, Copeland is setting the stage and creating a path for other dancers of color to feel as though they, too, can do ballet.

In addition to the groundbreaking leadership of Misty Copeland, I wanted to uplift some companies and programs that are prioritizing racial and ethnic representation into the world of ballet.

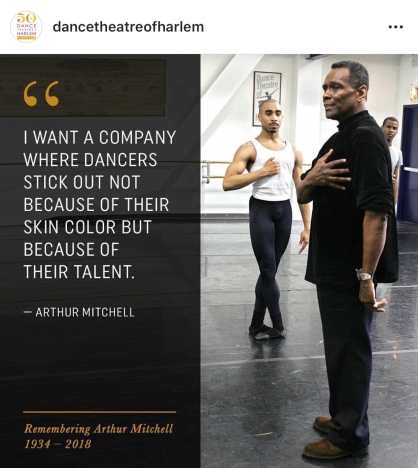

The Dance Theatre of Harlem (DTH) was founded in 1969 by Arthur Mitchell, who had previously been the first black male dancer in the New York City ballet. After the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. he realized that there was still work to be done in America in making a difference for black individuals. Mitchell created DTH to, “present a ballet company of African-American and other racially diverse artists who perform the most demanding repertory at the highest level of quality.” The Dance Theatre of Harlem is trying to bring down barriers between Harlem and the world of ballet and extend the art to communities that have been predominantly ignored within the field. Doing this requires that opportunities reach out to individuals who are also of different social classes to make ballet classes available and affordable. To do this, DTH started the initiative of Dancing Through Barriers to bring people of all ages from the community to learn about the arts through an inclusive and equitable arts education program.

Another example is Project Plié an initiative started by the American Ballet Theatre to create a community within the world of ballet where the talent of people of color could be nurtured. The company, “grant[s] merit-based training scholarships to talented children of color; provides teacher training scholarships to teachers of color [and] grants intern scholarships to young arts administrators of color.” American Ballet Theatre’s CEO, Rachel Moore emphasizes the importance of diversity both on stage and behind the scenes.

With both these initiatives working to bring more black dancers to the stages, there remains still the need to share the history and the stories of black dancers in America. MoBBallet makes it their mission to “preserve, present, and promote the contributions and stories of Black artists in the field of ballet, reinstating a legacy that has been muted.” Their website features a timeline of the various schools, performances, and companies that have provided opportunities for black dancers as well as access to an e-zine, or electronic magazine, to preserve the history and progress made thus far. Organizations such as these are integral to the preserving and showcasing the strides of black individuals in an accessible way.

https://www.abt.org/community/diversity-inclusion/project-plie/#images-5

https://www.abt.org/community/diversity-inclusion/project-plie/#images-5

As a Women’s Center intern, I see many parallels between the work that is being done at the Women’s Center toward advancing gender equity and the work that is being done by these companies and programs to advance racial and ethnic representation in the ballet community. Their approach is similar to that of the Women’s Center, as they acknowledge that to enact change, we need to prioritize and center the voices of those who have been marginalized to create an inclusive campus climate. At the Women’s Center, we see and acknowledge the harm that is done to the communities of people that are underrepresented and whose voices are repeatedly silenced. Many other articles written about this issue speak on the economic inequalities, racial prejudice, and racism that are foundations for the discrimination in ballet. (see links below)

In writing this blog, I urge my dance friends to look around their classroom the next time they are in ballet class and see where the privilege still lies. I hope that we continue to work on expanding the number of people of color in the classroom, both as teachers and students, to nurture a more inclusive generation of ballet artists. We should prioritize representation of individuals on stage and continue to work towards creating an inclusive ballet community off-stage as well, as ballet educators and choreographers.

We will only begin to see ballet transform when we acknowledge that this lack of representation is still so pervasive in Western society and encourage the next generation of choreographers to cast more diverse dancers. Everyone should have equal opportunities and equal access to be a part of this art form. As an aspiring choreographer and teacher, I will do my part in seeing that change through.

Additional Readings:

https://www.pointemagazine.com/behind-ballets-diversity-problem-2412811909.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/15/opinion/black-dancers-white-ballets.html

https://www.abt.org/community/diversity-inclusion/project-plie/

https://www.cnn.com/2018/05/21/us/misty-copeland-ballet-race-boss-files/index.html