A reflection by student staff member Shira Devorah

A reflection by student staff member Shira Devorah

By now, many of us have heard of that Pepsi ad with Kendall Jenner appropriating the Black Lives Matter movement.

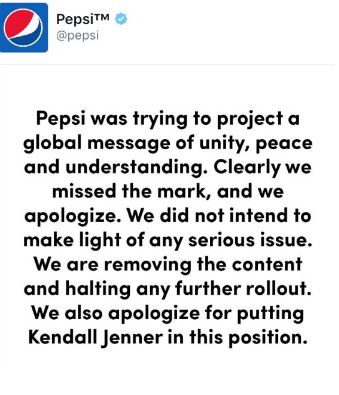

Immediately after the ad debuted, the internet blew up in opposition to it. Activists were not complacent with the whitewashed, safe, and commercialized rip-off of Black Lives Matter. Pepsi eventually issued a half-baked apology to the public (but mostly to Kendall Jenner).

I’m writing specifically about this advertisement as a sort of jumping-off point. I want to acknowledge, before moving forward into a broader discussion, the racism embedded in this ad. Kendall Jenner, a white woman, used black men (and the movement demanding justice for their lives) as props to support her image as an activist who could quell police brutality with a Pepsi. This is an example of overt racism in advertising.

A real- life example from the Baltimore Uprising in April 2015.

Racism in advertisements is not new. Soda companies have had a lot to do with this brand of racism. While this blog post is not entirely about racism, I think it is important to point out its presence before discussing other issues I have with this kind of ad.

What issues, you ask?

Co-existing with the obvious racism we can see in this advertisement, I want to talk about a different problem that this ad also brings up. I’m sick of seeing the way companies twist activist and feminist messages to sell products.

Companies appropriate feminist-ish narratives to make them seem like friendly, trustworthy, and progressive institutions.

Take the example of Dove’s body positivity campaign. Dove, the popular soap company, launched the “Campaign for Real Beauty” in 2004. This campaign has portrayed models for Dove products as more “realistic” depictions of women, as opposed to over- photoshopped, thin white models.

On the surface, this campaign looks pretty awesome. A company that’s not buying into sexist beauty standards? It absolutely sounds like a step in the right direction.

Yet there is a certain cognitive dissonance that accompanies the message Dove is presenting. On one hand, they’re telling me, “I’m beautiful just the way I am.”

On the other hand, I am being sold a beauty product specifically designed to make my body conform more to the beauty standards.

If Dove tells me I’m beautiful with my stretch marks while simultaneously selling me a skin-firming lotion, what message am I really supposed to be taking away from these advertisements?

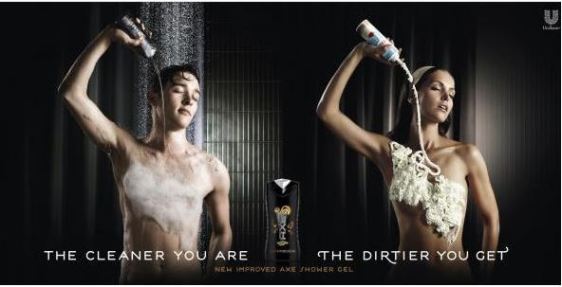

Additionally, Dove is a company under the corporation Unilever- the same conglomerate that owns Axe.

Axe is another soap product, but it is marketed in the completely opposite direction. Axe’s body sprays and hair gels are aimed towards teenage boys, and tend to use women as hyper- sexualized props to sell their products.

Screen capture from a recent Axe marketing campaign.

How can one company that espouses the empowerment of women be so closely tied to a another that uses sexist tactics to sell their product?

At the end of the day, major corporations like Dove, Axe, and their parent company, Unilever, aren’t people. They aren’t your friend, and they aren’t a magical way to get girls to like you. They are marketing teams targeting your passions and weaknesses in order to get you to buy their products.

At least with (many) small businesses, the stances that they take are likely the real positions that the founders have.

Take, for example, feminist owned bookstores in Baltimore, like Ivy Bookshop on Falls Road and Red Emma’s on North Avenue. These are small, independent businesses that are locally owned and operated. They actively employ Baltimore-based activists and provide space for discussion and performance.

When I go to Red Emma’s, I feel like I can have a legitimate conversation about body positivity with an employee and not be sold an answer. These are actually my fellow community members making a living in a broken system, selling an item with an actual meaning attached. Are they perfect? Absolutely not. But I feel more comfortable buying from them, knowing that they aren’t faking their commitment to a cause I care about.

This, of course, comes with another layer of complication. Buying from businesses who aren’t faking the activist narrative isn’t always possible (we learned that from the recent issues happening over at Thinx). There is a certain privilege that comes along with purchasing power. I wish I had the money to buy all of my books at Red Emma’s or soap from small businesses, but the companies that can afford to make/sell cheaper products are usually the ones I can afford.

So what am I getting at with this?

More than anything, I just want to bring awareness to the ways we are being used as consumers. If we realize how much power we have in our wallets, we can begin to be more aware of how our money is being spent.

Companies will always pander to us, but we can work to change the culture that companies are trying to appropriate. Maybe if we work to build a world that doesn’t rely on racist imagery or women’s bodies to sell products, we’ll be sold to in a way that is more on our terms as consumers. At the very least, being woke to capitalist agendas running our lives may help us maneuver the ways that we are sold to into a more positive light.

Want to learn more?

The Representation Project: Using film and media as catalysts for cultural transformation, The Representation Project inspires individuals and communities to challenge and overcome limiting stereotypes so that everyone – regardless of gender, race, class, age, religion, sexual orientation, ability, or circumstance – can fulfill their human potential.

Check out some documentaries exploring women in the media & advertising. Some recommendations include Miss Representation and Killing Me Softly (both available at the AOK Library!).

Here is a list of Black-owned businesses in Maryland.

Here’s how you can use SNAP at the Baltimore Farmer’s Market and Bazaar.