A blog reflection by Women’s Center student staff member Shira Devorah

A blog reflection by Women’s Center student staff member Shira Devorah

So I really love to talk about sex. It’s probably my favorite topic ever. I used to work for peer health education and with the sexual health committee at UHS here on campus. I’m considering becoming a therapist focusing on sex and relationships within the LGBTQ community.

I’ve always considered myself to be sex positive. But now I’m worried that identifying as such can be problematic.

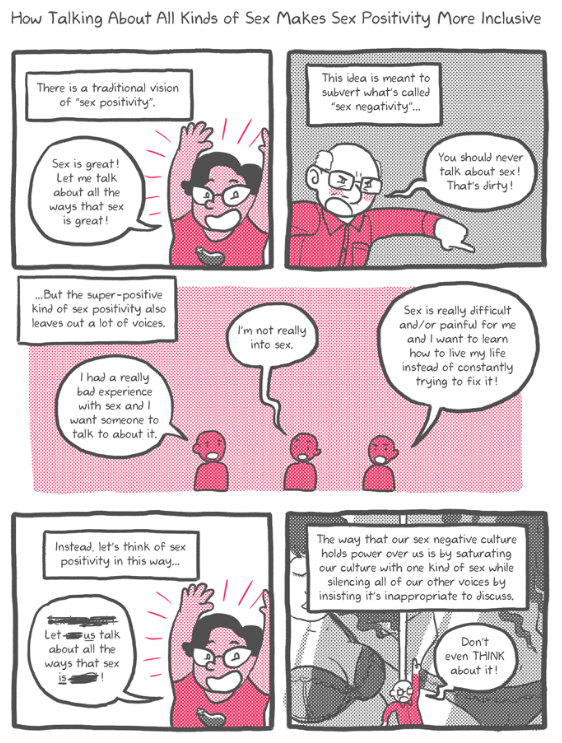

Sex positivity, in a really bare-bones sense, is a movement that unpacks our taboo notions of sexuality and embraces and promotes human sexuality and personal exploration. There is a huge emphasis on safer sex and informed consent, encouraging respect for people’s personal preferences and boundaries.

I’m definitely here for all of this.

But what are the limitations of this movement?

At surface level, sex positivity is a really cool thing. I feel confident discussing birth control options and my needs with friends and partners. Sex positivity has really allowed me to open myself up as a person and not deny my interest and care about this subject. The fact that this movement exists means that I can one day work in a field devoted to improving sex lives for LGBTQ people.

But sometimes I wonder if I really want to call myself sex positive anymore. Is being sex positive actually accessible to other people?

Although in theory sex positivity creates space for all people to explore their sexuality, in reality these conversations are not always accessible for everyone. There are many reasons sex positivity isn’t everyone’s cup of tea, even though it may be mine.

It’s difficult for women to be open about sexuality without some sort of pushback, and it can be especially challenging for women of color.

There are a lot of negative stereotypes surrounding women who choose to reclaim their own sexuality through sex positivity. First off, women who identify as sex positive often get sex shamed for their openness discussing these taboo topics. People tend to make a lot of assumptions about women who are open with their sexuality – that we’re ‘slutty’, interested in casual sex, unfeminine, or the object of male desire. These looming misconceptions may turn women off to the idea of being sex positive.

Although I may encounter some of these problematic assumptions, because I’m a white woman(ish) I’m not ever racially stereotyped based on my openness with sexual topics, which can be a reality for many people of color.

Many women of color are fetishized based on their race, and so they may feel more conflicted about associating with this term. For example, black women are often stereotyped as hypersexual, while Asian women are stereotyped as submissive sex objects. Since women of color are often already sexualized in troubling ways, sex positivity might make women of color feel more ostracized. Franchesca Ramsey has a really great video on sexual and dating racism you should check out here.

Feminista Jones from her website, feministajones.com

Some activists, like Feminista Jones, a Black feminist sex positive blogger, have helped counteract this narrative within sex positive circles. Jones has written about subverting the idea that Black women are hypersexual. In her piece “From Slavery to Sexual Freedom,” Jones discusses embracing Black female sexuality is an act of defiance against the fetishization of women of color. This is one example of how sex positivity can be reclaimed as an intersectional term – but this still doesn’t solve the systemic issue of racial sexualization.

On a different note, I’m also mindful about potentially alienating asexual people and survivors of sexual violence. Sure, I absolutely love being an open book when it comes to sex and sexuality. This means that I talk a lot about sexuality in a variety of different ways; I feel comfortable discussing the educational aspects of sexuality, like teaching people about consent or how to use contraceptives.

Still, I sometimes find myself discussing less ‘academic’ aspects of human sexuality. I am comfortable with pretty personal conversations, but a lot of people may not be. Some people may even be triggered by these conversations.

Of course, there is a vast difference between discussing safe sex and talking explicitly about sex with friends. Still, the line between informative sexual discussions and casual and potentially invasive discussions may be difficult to draw – especially if you’re like me and never stop the conversation. For close friends, I have a better understanding of what their boundaries are, and know what is and is not appropriate to say. These kinds of discussions are very different than those concerning contraception, which can be appropriate based on who is having this conversation, which spaces they are taking place in. In spaces that are more public, it is possible that people may overhear and be triggered by my discussions. Sometimes conversations that aren’t sexually explicit may still be troubling to some individuals. I need to stay tuned to the needs of all people who may be present.

I don’t know everyone’s stories, and it’s not my business to know their trauma or identity. It is, however, my business to be courteous and kind – and my loud, boisterous chats about contraception might not be as enjoyable to someone else as it is to me.

So how can I problematize sex positivity while continuing to associate with the movement?

I think I need to re-define what sex positivity is to me. It is all that I have grown accustomed to, but so much more. My kind of sex positivity is an inclusive one, accessible to all bodies. My sex positivity is open and honest, but should not be loud nor in-your-face. My sex positivity reclaims sexuality, but understands how sexuality can be misused and feed into rape culture and patriarchy. Most importantly, my sex positivity is my own, and I do not have have to expect other people to see things the way that I do. It does not make them any less of a feminist to feel uncomfortable with sex positivity, it just makes their lens different.

art by Ronnie Ritchie, for everyday feminism

I would really love to reconcile with the term “sex positive” while being mindful that this identifier is not always accessible, realistic, or even as positive as the title claims.

I must be critical of the limitations of being sex positive. I want to expand my awareness for who is included and who gets left out of this narrative. My sex positivity needs to include all bodies, all genders, and all sexualities. In order to reconcile with my own sex positivity, I must remember that it is not the one right way to be a feminist.