What gets you up and out the door each morning? And what makes a job more than a job—or even more than a career? For so many who make UMBC their professional home, the value goes way beyond a paycheck.

Case in point: Employees for the 14th consecutive year rated UMBC as one of ModernThink’s Great Colleges to Work For in all 10 categories, including shared governance, mission and pride, job satisfaction and support, and diversity, equity, and inclusion. Additionally, the Baltimore Sun has once again named UMBC a 2023 Top Workplace winner based on a confidential employee survey conducted earlier this year. This is the 9th time UMBC has earned this designation since 2013.

What does this excellence look like in the day-to-day? We talked to some Retrievers about what they love about their work at UMBC.

Want weekly Top Stories sent to your inbox?

Valuing Our Whole Selves

UMBC is a place that considers the whole person, opening up space for both professional growth and work-life balance. From mentoring programs to embracing our individual stories, when we support each other in our work and lives, we all come out stronger.

Sharing Our Time

Dozens of Retrievers spent time this fall planting 900 new trees around campus, including those pictured here (L-R): Gavin Gilliland, Abby Hart ’18, and Tim Olivella.

Building bridges across campus

They met so many times at Starbucks, they knew each other’s orders.

Damian Doyle (’99, computer science, M.S. ’16, information systems): tea, Earl Grey, hot. Charlotte Keniston (M.F.A. ’14, intermedia and digital arts): coffee, iced.

Over their caffeine of choice, the two UMBC staff, who work in wildly divergent disciplines, forged connections through the Professional Staff Senate mentorship program—a staple of campus connectedness for the last decade.

Doyle, who works in information technology and has been a staff member at the university for almost 24 years, has served as a mentor for more than five years. Keniston, who started at the Shriver Center five years ago, anticipated a year of opportunity and transition and wanted a mentor to guide her toward balance between a demanding career, family, and finishing her Ph.D. in language, literacy, and culture.

“It was a perfect fit because Damian saw the big picture of the university and explained the campus overarching structures that I had never understood and was really great at advising me on critical points I was at in my career,” Keniston said.

As a mentor to a number of staff over the years, Doyle finds the program rewarding.

“One of the things I loved was getting to know different parts of the university. I get exposed to these different areas of the campus at a deeper level. It confirms for me the kind of driven work that people are doing.”

The mentorship program matches staff through a mentee-first pairing system that includes a speed-dating session and goal analysis for a year-long commitment. Keniston said the mentorship was crucial to her path at UMBC.

“I was at the point where I felt like I couldn’t ask questions, like, ‘Who is this person?’” Keniston said with a laugh. “But being in this mentor/mentee relationship gave me an opportunity to say, ‘Help me understand this.’”

Doyle said that hearing Keniston’s questions and seeing the campus organization through new eyes helped him know what is working and what needs improvement at UMBC. “It’s very educational for me, having to think through what is the right answer, what is the honest answer.”

After a year of meeting about once a month, Doyle has a new mentee, and Keniston has now become a mentor. But they’ll be keeping in touch. Maybe over tea and coffee.

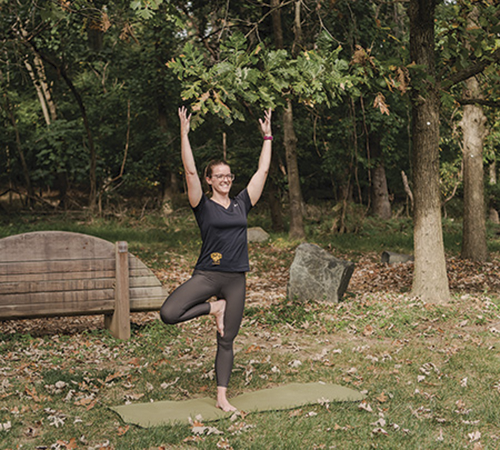

Inner Peace

Many of our staff and faculty take advantage of free exercise and wellness classes in the RAC, some of which are taught by Joella Lubaszewski ’10.

Telling her authentic story

Melessia Jasper’s journey to UMBC was not straight. But something kept pointing her toward UMBC. And toward herself.

“My path to UMBC started before I knew about UMBC,” Jasper said, explaining that after high school in Alabama, she arrived in Maryland only to find that the job she had been promised was locked in a hiring freeze. She started at American University, where she worked with two former UMBC staffers. Then she heard UMBC President Emeritus Freeman Hrabowski at a faculty retreat. “I didn’t realize it at the time, but God was laying the groundwork for where I am today.”

When she moved to Baltimore with her new husband, she applied to UMBC and worked in several different divisions, including Student Affairs and Administration and Finance. In each office, Jasper said, she found acceptance and growth. She now works in the Division of Institutional Equity.

“It was the first university I worked for where you’re applauded for your quirkiness,” Jasper said. “I was so empowered by the resources UMBC offered to me that I then could empower others.”

Last year, she stood on stage to tell her story in a Retriever Talk. For weeks, she and a cohort of other UMBC staff labored with Jill Wardell ’99, interdisciplinary studies, and other strategic talent management and storytelling staff to shape their life tales, a commitment of time and effort on the part of both the storytellers and for UMBC. Jasper said she felt like she was stripping naked. She was reluctant but told herself, “Sometimes, you have to be uncomfortable in order to follow your purpose in life.”

In addition to revealing lifelong intrusive thoughts of inadequacies and imposter syndrome, Jasper also shared—in front of hundreds of people she didn’t know—that in 2000, doctors discovered she had a rare condition called a Chiari malformation, in which part of her brain had grown down into her spine. Her doctor was amazed at what she had achieved, but Jasper knew she was only getting started.

After her Retriever Talk, many students, colleagues, and even strangers have since contacted her to affirm how her story helped them.

“This is something that I have gone through,” Jasper said. “If I can go through it and possibly help you by telling you my story, I want you to have that same freedom…freedom in understanding who I am and accepting who I am.”

A Community That Builds Together

Through our unique commitment to shared governance and a deep appreciation of community, we collectively build UMBC into what we know it should be.

Sharing the Moment

The annual cookout put on by the Professional Staff Senate and Nonexempt Staff Senate brings folks together from all over campus.

Finding a voice in leadership

There’s a reason the Nonexempt Staff Senate (NESS) carries the name of a democratic body. Alongside other staff and faculty shared governance groups and student government bodies serving their respective constituents, NESS exists to ensure all UMBC nonexempt employees have a voice, the way democracy is supposed to work.

Desiree Stonesifer, serving the second year of her term as president of NESS, and a business services specialist in the financial services department, believes that the shared governance organization builds trust at the university. UMBC offers both staff and faculty shared governance groups, in which all parties work together on the university’s leadership.

“I think it gives people the security of knowing that they’re welcome to speak their mind without it being held against them,” Stonesifer said. “They’re allowed to have thoughts outside the status quo. And a lot of times, those are the kind of thoughts that maybe the administration or other people in the university haven’t thought of. It gives everyone different perspectives and it allows staff the ability to grow more comfortable in their community so that they can be who they are and say what they think.”

NESS helps its members handle issues that are vital to employees: Are job descriptions adequate? Are positions equitably valued? Is professional development available?

Many of the nonexempt senate members aren’t interacting with students as much as other UMBC employees, Stonesifer said, and many of them want to reach out. The NESS, she said, can help members “find ways to get involved in the community.”

Creating Change

Campus offices like the Center for Democracy and Civic Life work alongside students to engage the community and make a difference.

Creating a green space of solace

Charles Hogan, UMBC’s landscape and grounds manager, is comfortable with trees. He grew up climbing them, building forts in them, and “falling out of them,” he said, laughing. For decades, he has run and biked through forests for mile upon mile every week.

As he walks UMBC’s Academic Row in his sturdy boots and cargo pants, Hogan (above, right) admires the trees that have survived years of building renovations, root system compromise by tunnels carrying utilities and water underground, and the hundreds of students who tramp over their soil and tie hammocks to their trunks.

Hogan, who has worked on UMBC’s landscaping for 26 years, likes to construct park-like pockets dotted throughout the campus. Each of those miniature parks is based around trees, whether that’s the pair of oaks in front of the Administration Building that tower over the hydrangeas below or the diminutive weeping redbud that Hogan wanted to top with a tiny hat and sunglasses because it looked so much like Cousin Itt from the Addams Family.

“I’m a tree person,” said Hogan, who is a certified arborist. “Trees should be the focal points. We’re creating a lot of little park environments.”

A campus’ green spaces, Hogan said, make a difference when students and their families are trying to decide where to attend as well as provide succor to everyone making their way through a busy semester. That’s why the grounds staff plants 30,000 summer annuals and 10,000 fall pansies every year. Each area on campus is assigned to a particular gardener, Hogan said, who takes pride in the beauty of the plants under their charge.

Those gardens and the shade of the trees surrounding the buildings offer comfort to the staff, faculty, and students who make the campus their living rooms.

“I never went to college, but I know students are under a lot of stress. They should be able to sit outside, read, study, write a paper,” Hogan said. “Any landscape, whether it’s at your house or on campus, should make you feel good, feel relaxed.”

Living the Mission

At the end of the day, UMBC’s values and mission are what bring us all together. When we work in service of our students and our academic mission of inclusive excellence, it’s hard not to feel connected to the work on another level.

A Student-Centered Community

At the beginning of each school year, our new students are officially welcomed with the Convocation ceremony, where they each receive a special UMBC shield pin.

Lifting students to the next level

When he’s deep into extolling the mission and benefits of the McNair Scholars Program he directs, Michael Hunt ’06, computer engineering, needs only a pulpit to become the preacher he trained to be.

When Hunt sees a student achieve, he feels “that parent feeling, that joy that comes to you. Sometimes I’m more excited than they are when they’re telling me. Sometimes it’s a sense of awe in knowing their story, in knowing all that had to happen to get to that space,” said Hunt, who has a masters in theology. “I feel like we’re the mama bird, teaching them all they need before they fly away.”

The federally funded McNair program, with a goal of boosting students from underrepresented segments of society into earning research-based doctoral degrees, has expanded over the six years of Hunt’s directorship.

Every year, the McNair Scholars Program funds 30 slots for students, who meet with mentors, fulfill service obligations, attend cross-cultural events, and receive the help they need to prepare for, apply to, and excel in graduate school.

Hunt, who was a Meyerhoff and McNair scholar, is earning his own interdisciplinary Ph.D. from UMBC. After he became director of the McNair program in 2019, he found himself frustrated when he had to shut some students out of opportunities. So he spearheaded, with the backing of the then-current scholars, staff, and McNair Advisory Council, the creation of the Friends of McNair network, a group of students who reap some of the mentoring, community, and support benefits that McNair Scholars enjoy.

Hunt is exploring ways for the university to expand the support it gives to students not in formal scholar programs. He enthusiastically advocates for the need for holistic critical mentoring (HCM), a network of power-dynamic-flipped, student-centered, reciprocal relationships. HCM is the mentoring framework that uplifts both mentor and mentee while dismantling systems of oppression.

“Because of my heart and because of the work that I do, I don’t want to turn anyone away when I know there are resources to support them. The institution has to rise and say, ‘This is a part of the work of inclusive excellence, and we’re going to fund this to make it happen.’ What I love about my institution is that the more I talk and have these conversations, the more I do see people beginning to question and challenge what we are doing. And so I don’t feel quieted. In other spaces, I know that folks would have been quieted.”

Moments of Joy

There’s simply nothing like the feeling of watching our students cross the stage to get their diplomas.

Shaping success in all sizes

At Commencement, Kyung-Eun Yoon likes to sneak out of her academic division’s seating section to hug students in other majors, she confesses. Of course, she gets to hug all the Korean majors when they rise to receive their diplomas, but other students have taken maybe five or six courses or minored in Korean, and she wants to embrace them, too, to recognize that achievement.

Student success, Yoon says, doesn’t come in one shape or size.

“For some students, yes, excelling in every class and getting double degrees and finishing an honors program with a wonderful thesis, going to Korea’s top university as a graduate student, getting a job—that’s a wonderful, wonderful success story,” Yoon said. “But for some students, completing the semester without withdrawing from too many classes, or without failing one or two courses, completing their degree, finally, in five or six years, that’s a wonderful success story for them too.”

Yoon started at UMBC in 2009 as the coordinator of the new Korean program and has grown the program so that students can now major or minor in Korean within the modern languages, linguistics, and intercultural communication department. Over her 14 years, Yoon’s Korean program graduates have gone on to work at the National Security Agency, to pursue graduate schools in various fields including Korean studies and international relations, to teach English in Korea, and more.

But sometimes, she said, success looks like one student whose achievement she particularly treasures. The student had dropped out, withdrawn from many classes, but after six years and many advising sessions with Yoon, last May, she graduated.

“It was not just a mere graduation for her, it was a really, really huge success for her,” Yoon said, and that student’s achievement made Yoon feel proud. “I did this much,” she says, holding up her finger and thumb an inch apart.

Yoon and her colleagues can help students along the path of hard work, but eventually, she says, “you have to have your ownership. We’ll help you, but without your ownership of this time, success cannot be happening.”

And when success happens, Yoon is sure to find that student to give them a hug.

By Susan Thornton Hobby