A nine-year-old stands at the mouth of a coal mine covered in coal dust, wearing a small headlamp. A woman holds her baby on her lap as she packs boxes in a warehouse along with her 5-, 8-, and 12-year-olds. These are just two of thousands of evocative black-and white historical photographs handled by Special Collections interns Meredith Power ’21, history, a public history graduate student, and Gabe Morrison ’23, anthropology. Along with library staff members, these two worked diligently to ensure that the images of the families and children who lived through these harrowing work conditions are accessible to the public for research and learning.

Fine motor skills

“Photos from the early 1900s were developed on fine photographic paper that is prone to crinkling around the edges, ripping, and fading,” Power says. Wearing blue nitrile medical gloves, they rehouse photos from their cellophane sleeves to museum-grade mylar sleeves, keeping them from further discoloration, tears, wrinkles, and sticking to the sleeves.

“They’re very delicate,” Power says. “You need good eye-hand coordination to pick up the photos from the corners, remove them from whatever packaging they are in, and slide them into the mylar sleeve.”

Power puts the historical photos into a mylar sleeve. (Marlayna Demond ’11/UMBC)

Power puts the historical photos into a mylar sleeve. (Marlayna Demond ’11/UMBC)

This process is second nature for Morrison, who has been working at Special Collections for over a year. He has worked with securing the Lewis Hine photos as part of his public humanities minor, as well as the Maryland Folklife Program Collection, the Coslet-Sapienza Fantasy and Science Fiction Fanzine Collection, and the George Cruikshank illustrations and papers.

“I had to learn how to properly handle photographs and manuscripts and how to catalog them according to the Library of Congress classification system,” Morrison says. For both Power and Morrison, developing greater patience and manual dexterity and embracing working through hundreds of documents alone in a quiet space surrounded by stacks of materials was well worth the effort to broaden access to these historic documents.

“The value of this project is ensuring people understand that this resource exists,” says Power, “to help these photos live beyond a heavily controlled and restricted space on campus into a digital space where more people are able to access the information.”

Digital accessibility

Protecting delicate, historic documents includes digitizing them. The digitizing process is another lesson in precision and patience. Power begins the process by taking a photo out of the mylar sleeve—making sure to only touch the corners—along with a small rectangular white piece of paper describing the photo. They gently place the photo underneath a camera, delicately straightening the image before the camera snaps the picture and sends it to a computer where Power edits it using Adobe Lightroom.

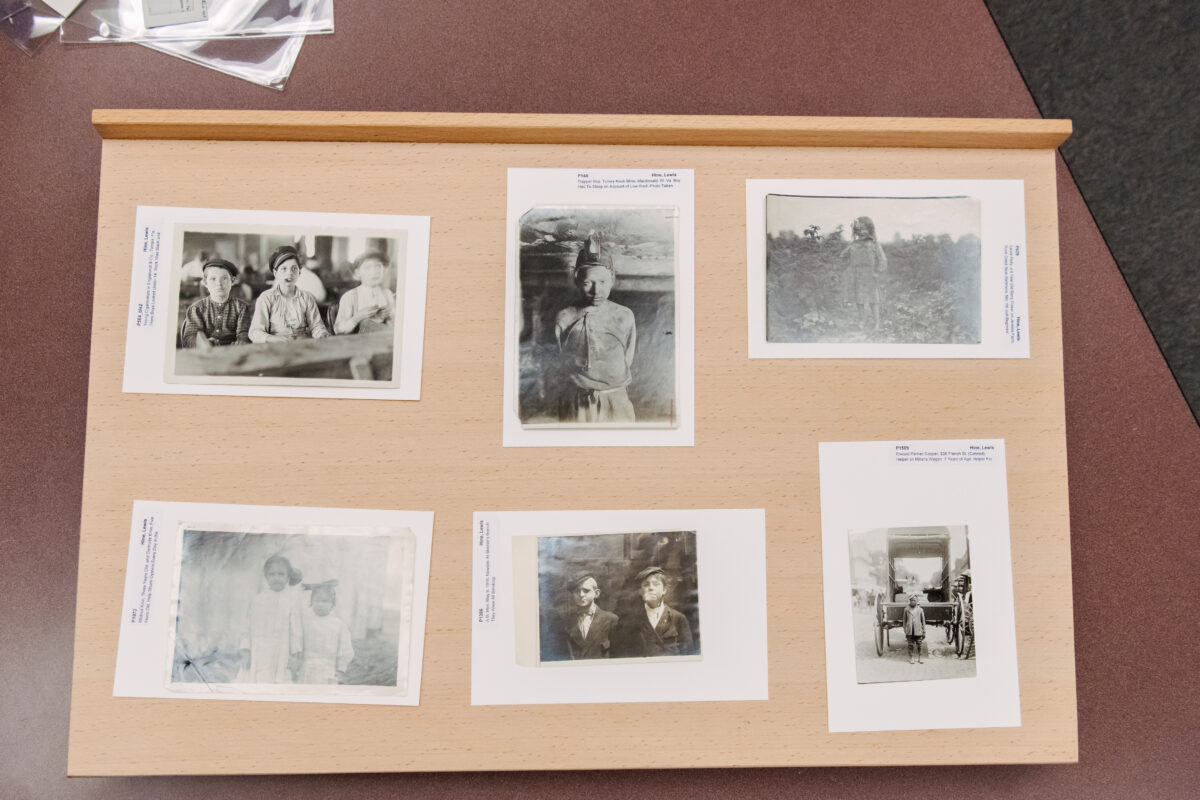

A small collection of the 5,400 photographs that were digitized and rehoused in more protective plastic sleeves. (Marlayna Demond ’11/UMBC)

A small collection of the 5,400 photographs that were digitized and rehoused in more protective plastic sleeves. (Marlayna Demond ’11/UMBC)

“It’s an elaborate setup with lights at 45-degree angles, and the camera pointed straight down at a small white stand where I place the image,” explains Power, who would work on digitizing for six to eight hours at a time. “Once I take the image, I edit the size and angle of the photo. The metadata is then added into an Excel spreadsheet, which includes noting if there was a corner missing or if the photo had adhesive stuck to it.”

Digitizing rare books, something Morrison has spent months working on, requires using a special book scanning machine with raised sides, like hands cradling the book open, and small snakelike bean bag weights to keep the pages flat without using his fingers. “I make sure I’m not blocking any text or any important image. And then I press a button, flip a page, press a button, flip a page for hours on end until I finish digitizing that book,” Morrison says, smiling. “So, it’s not the most exciting work, but I find digitization specifically important because it’s a process that helps preserve documents too fragile to be in public circulation. Digitally, you can share it with a broader audience.”

Workforce skills

Both Power and Morrison brought many special collections skills to their public humanities internships. Archaeology camp inspired Morrison to learn about how to study and take care of important and fragile objects. He worked at the Montgomery Parks Archeology Program throughout high school, where he met a friend who introduced him to UMBC’s Special Collections. “I’ve always had an interest in historic things, in the preservation of artifacts,” Morrison says, who plans to apply to a master’s program in library and museum studies after graduation. “I think Special Collections has helped me realize I want to do archival work.”

Power found their footing working full time in the conservation rooms at Baltimore’s Walters Art Museum. “I was the administrative assistant in the Conservation Division and was around a lot of conversations on handling art objects and special collections materials, but I did not work with the materials directly,” says Power. “Working with the Hine Collection was a great opportunity for hands-on experience working with physical items and digitization.” These skills have also come in handy for Power, whose master’s degree focuses on 14th-century religious women hermits in Yorkshire, England. In 2022, Power had the opportunity to visit parish archives in Yorkshire to read through medieval-primary source documents.

For Power, history isn’t just books, dates, and lists of events. They say that there are a lot of living materials out there, whether that’s parish churches or photographs from the early 20th century, like the Hine collection. There is a connection between public history work and the people who lived before us. “It’s important to continue to help students remember that history is not dead and dusty. It’s alive,” says Power. They feel that the connection element is essential, and sometimes it gets lost. “Special Collections prove that these events really happened. They can inspire students to visit those places. To stand in that space where it happened and say, ‘Yeah, I was here too.’ I love that.”