Mold on your bread or bathroom tiles can be a nuisance. Mold in a scientific lab can be a marvel.

Up close, the growth of mold becomes living artwork—white, feathery shoots morphing into undulating waves of color. And molds can be amazingly useful.

“They are used to ferment food, make laundry detergent enzymes, and help produce pharmaceuticals,” explains Garrett Hill ’24, biochemistry and molecular biology, who has been working with molds in the research lab of UMBC chemical engineering professor Mark Marten for more than four years. “It’s surprising how ubiquitous they are in industry.”

Molds (along with mushrooms) belong to a group of organisms more technically known as filamentous fungi. One of the oldest and largest living organisms in the world is a filamentous fungus, nicknamed the “Humongous Fungus,” that has likely been spreading across the Blue Mountains in eastern Oregon for more than 2,000 years, and has come to occupy an area of more than 2,000 acres.

The Humongous Fungus grew (and grew) through an enormous network of interconnected thread-like structures called hyphae that gather and share vital nutrients.

Networks—of a different sort—are also vitally important to the students studying fungi in Marten’s lab. Lab members, from high schoolers to Ph.D. students, work together on projects. Marten offers advice not only on research questions, but also on skills such as communication. Support flows in from the university, in the form of research awards, scholar programs, and more. It’s tied together with a simple philosophy that helps everyone flourish: “Mentorship is the magic ingredient,” Marten says.

High school research leads to UMBC

Hill found his way to Marten’s lab through a program in nearby Howard County Public Schools called the Biotechnology Career Academy. As part of the program, he earned credit for conducting research in the lab. After high school graduation, he enrolled at UMBC and has continued his work in Marten’s lab every year since.

“UMBC has a culture that emphasizes supporting students,” says Hill. “This was something that initially attracted me to the school, and something that I’ve absolutely experienced during my time here.”

In Marten’s lab, Hill has been working on research that investigates how a fungus called Aspergillus nidulans repairs damaged cell walls. Armed with a better understanding of the complicated cascade of biochemical reactions triggered when the fungal cell wall is damaged, scientists could possibly manipulate the process to use molds more effectively (or in the case of harmful molds, eradicate them more effectively.)

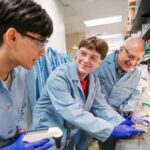

Mark Marten (left) and Garrett Hill examine mold cultures. (Marlayna Demond ’11/UMBC)

Mark Marten (left) and Garrett Hill examine mold cultures. (Marlayna Demond ’11/UMBC)To untangle the hidden and complicated inner workings of the fungus, the researchers deploy an arsenal of analytical tools and methods.

“When I started in the lab, I spent a lot of time learning the background and standard lab techniques,” Hill says. “But now that I’ve had a few years to acclimate, I have the foundation to support my own project.”

As part of that project, Hill has been investigating how to use the Nobel Prize-winning gene editing tool called CRISPR to create fungal cells with inner elements that light up. The light provides a beacon for researchers to track how those elements move as the cell experiences stress or initiates repairs.

“The sense of project ownership has been one of the most rewarding parts of my research experience,” Hill says. “When my graduate mentor and I first discussed the possibility of leading my own project, I had a brief moment of doubt. But I chose to not listen to that voice.”

Networks nourish growth

Hill says he was attracted to the beauty and power of science from a young age, even though no one in his family had a scientific career. UMBC has provided the resources and counsel to help him chart his path.

Within Marten’s lab, Hill says more experienced researchers were always willing to help. When Hill first joined as a high schooler, fellow lab member Ryland Spence ’19, biological sciences, who is now a medical student at Brown University, trained him on techniques.

“Mentorship has been so important for me, so I am always happy to provide mentorship to others whenever I get the chance,” Spence says. “A supportive environment that values diversity is very much a part of UMBC.”

Marten himself also provided enormous guidance and support. “Dr. Marten has been the strongest mentor I’ve had, helping me even before I came to UMBC,” Hill says. “He’s taught me not only about fungus, but also about how to think like a researcher, how to present research, and how to be a good student.”

University-wide programs provided Hill with additional research support. He was awarded multiple Undergraduate Research Awards (URAs), which provide financial assistance for research projects and opportunities to practice skills such as presenting research.

Hill is also part of the nationally renowned Meyerhoff Scholar Program, which seeks to increase diversity among future leaders in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics by supporting students who intend to pursue a Ph.D. or combined M.D./Ph.D. in STEM and are interested in the advancement of minorities in those fields.

“A lot of my best friends are from the program,” says Hill. “It’s been great to have that community.”

Now that he is applying to graduate schools, Hill says the Meyerhoff program provides detailed guidance through the process. “They have been an invaluable resource, and a rock really. They make sure I know what I need to do now to ensure I have opportunities in the future.”

A closing chapter and a new beginning

As the fall semester of his senior year kicks off, Hill says that he’s feeling confident and excited.

“I find myself frequently looking back on how I felt on my first day in the lab, during my first lab meeting presentation, or during my first day of classes, and realizing how much I’ve grown these past few years,” he says. “What once used to really shake me, I am now able to do with confidence—that tells me a lot about what I’ve gained from my research experience.”

As Hill gears up for grad school, he is passing the baton to other UMBC students like Matthew Quintanilla ’27, chemical engineering, a first-year student whose journey shares many similarities with Hill’s. The first in his family to pursue a scientific career, Quintanilla also started work in Marten’s lab as a high-schooler and decided to enroll at UMBC. In Marten’s lab, Quintanilla is working with Ph.D. student Alex Doan, who attended the same high school and embraced the opportunity to mentor fellow students.

“It’s been great catching up on high school news, but more importantly helping students grow,” says Doan.

Matthew Quintanilla works in the lab. (Marlayna Demond ’11/UMBC)

Matthew Quintanilla works in the lab. (Marlayna Demond ’11/UMBC)Quintanilla is also a URA-recipient and Meyerhoff Scholar, and says he is excited for the new school year.

“I am eager to start my academic career at UMBC, meet many others, and integrate my knowledge from courses into my lab work,” he says.

“Matthew and Garrett are both really talented individuals,” says Marten. “Having them in the lab has been a win-win situation.”

April Householder ’95, the director of undergraduate research and prestigious scholarships at UMBC, looks at Marten’s lab as a microcosm of the vibrant UMBC research environment. “These two students—Garrett and Matthew—represent two ends of the research spectrum. One is just getting started, and the other is a four-time URA Scholar,” she says.

“The support these students receive from the mentorship in their lab is invaluable, but also as important is the peer-to-peer support they will get from one another. It’s this type of academic community building that gets student researchers excited about being a part of UMBC.”

Mold under the microscope. (Image by Kathie Hodge

Mold under the microscope. (Image by Kathie Hodge