Seven years ago, Mejdulene Bernard Shomali began a search for her queer Arab women “banat” ancestors. Shomali, a queer Palestinian poet, was looking for mirrors and searching for hope in other queer Arab women, queer Arab banat. Their lives and names were unknown to her, blurred as they were by Western, Orientalism, and Arab hetero-patriarchal representations of Arab femininity.

Shomali came to UMBC in 2015 as a member of the third cohort of UMBC’s Postdoctoral Fellows which recognizes and supports talented scholars who are emerging as cutting-edge researchers and educators in their fields. In 2016, Shomali joined the faculty as an assistant professor of gender, women’s, and sexuality studies.

Shomali wondered if one could be queer and Arab and okay all at the same time especially if representation of queer banat desire was missing from popular cultural texts and films. In the darkest of times, during a global pandemic shutdown, she found her answer— it was a resounding, YES. Not only can one be queer and Arab and okay, you can also create queer Arab joy.

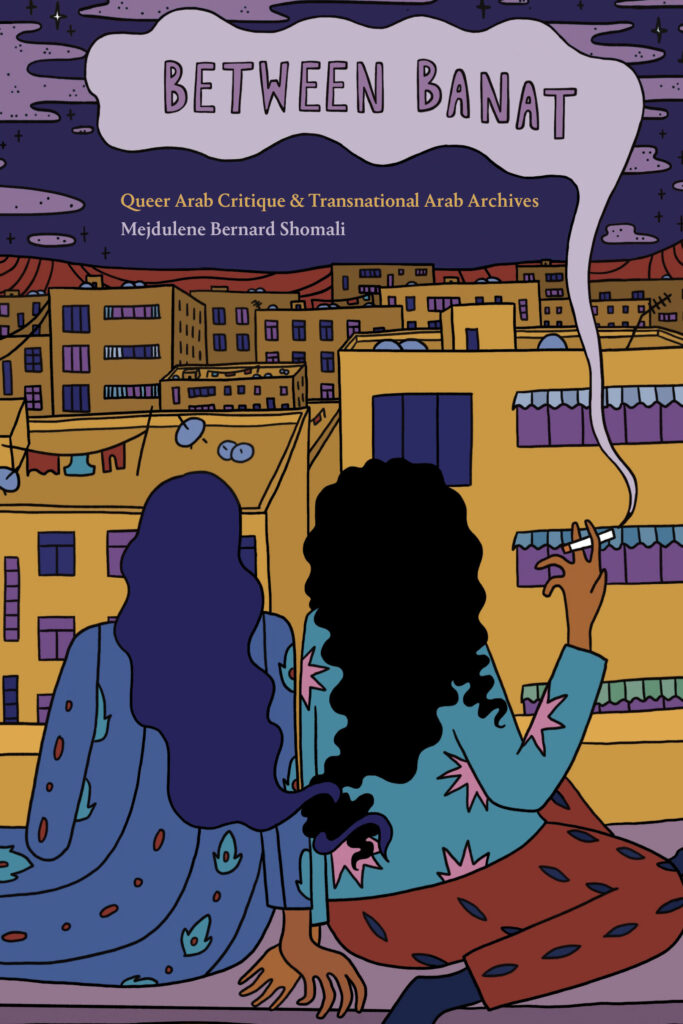

In 2019, Shomali received The Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation Career Enhancement Fellowship to continue research for her manuscript. After seven years of research throughout the Arab diaspora, Shomali published her first book, Between Banat: Queer Arab Critique and Transnational Arab Archives. It is the first study of desire that addresses the contemporary cultures and lives of queer Arab women.

Book cover illustration by Aude Nasr.

Book cover illustration by Aude Nasr.“This book is my love letter to my unnamed queer Palestinian ancestors. It is the knowing glance, playful wink, and double entendre between us,” Shomali writes in her book. “It is the ways we call one another, not only for recognition and community but to action and movement toward a joyful and pleasurable queer Arab future.”

Shomali, who has developed university-wide programming around Arab and Muslim identity, discussed her book at the Dresher Center for the Humanities 2023 Spring Humanities Forum. “It is not easy to work at the intersection of several disciplines and build both sophisticated and intelligible arguments for all audiences,” said Carole McCann, professor and chair of gender, women’s, and sexuality studies, who introduced Shomali. “However, Dr. Shomali deploys the conceptual tools of critical cultural studies, literary theory, transnational feminist theory, and queer of color critique with great dexterity demonstrating both a sharp intellect and immense writerly talent.”

Queer Arab Critique

Moving between Arabic, English, and Arabish (Arab+English), Shomali takes us as far back as the 10th century to analyze the famed Persian, Arab, Indian, and Asian tale of The Thousand and One Nights where Scheherazade saves herself, other women, and the nation by telling the king—who killed his virgin wives each morning—stories over 1001 nights. “As a storyteller and state queen, she evades the three typical representations of Arab femininity: silent veiled Muslima, hypersexual dancer or harem girl, and female terrorist,” notes Shomali. “She is hailed as an ancestor, muse, and icon for many Arab and Arab American writers.”

Shomali analyzes an 1855 and 1995 translation and three modern versions. “Scheherazade has also been used as a key figure in the portrayal of Arab women’s femininity, elitism, heteronormative sexuality, and anti-Blackness and has served to perpetuate colonial and Orientalist beliefs of the Arab world,” explains Shomali. Orientalism defines the West as civilized colonizers with progressive ideas and the East as foreign, uncivilized, primitive, and “other” that must be tamed through colonization. “Studying Scheherazade can reveal how representations of Arab women and femininity change given the cultural and political context in which they emerge,” says Shomali.

Where would one find queer Arab representation in a text that defines heterosexuality as the norm of Arab femininity? Like many queer people and people of color who do not see themselves represented in literature, art, business, or academia Shomali had to design her own solution—what she calls a Queer Arab Critique.

Queer Arab Critique is about finding the unseen, “the what ifs,” reading critically and between the lines. Using this lens, Shomali reexamines Scheherazade’s story and two films from the Golden Era of Egyptian Cinema (1940s – 70s). It is as much a mirror for queer Arab women of queer Arab women’s desires, sexuality, space, and time. It is also evidence that Western colonization and Western queer thought do not define nor erase mainstream queer Arab culture.

“Queer Arab Critique allows us to see the traces of queer desire in mainstream Arab cultures and undermines the erasure of queer people from Arab histories,” Shomali explains, “and reveals how queerness and Arabness are constructed relationally, between many locations, texts, and times.”

For and by queer Arab women

Between Banat is equally about undoing the archives of the past as it is about creating a new queer Arab archive. One that centers on literature, arts, film, and activism by and for trans and cis Arab women, femmes, and those Arabs who identify with femininity.

Searching for these vibrant communities pre-pandemic would have taken multiple trips to several countries, scouring state and local archives, and finding the hidden and active network of queer Arab communities. A global pandemic meant shifting gears. Shomali took to digital sleuthing in English and Arabic. Posting questions, following helpers, and clicking through online bootleg archives in Lebanon, Syria, Saudi Arabia, and Palestine.

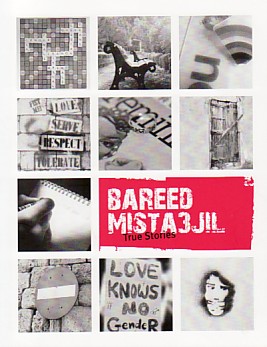

“Bareed Mista3ji” by Meem.

“Bareed Mista3ji” by Meem.One find includes three biographical essay collections: “Haqi: An A’ish, An Akhtar, An Akoon” (My Right: To Live, To Choose, To Be) and “Waqfet Banat” (Women’s Stand) by Astwa in Palestine, and “Bareed Mista3ji” (Priority Mail) by Meem in Lebanon. Through anonymous and first-name authorship, banat write about their experiences, identities, and communities and publish their work via queer feminist organizations that advocate for LGBTI+ communities like Astwa and Meem.

In her search, Shomali also found three novels: Elham Mansour’s Ana Hiya Inti (I Am You), Seba al-Herz’s Al Akharuun (The Others), and Samar Yazbek’s Ra’ihat il Kirfathree (The Scent of Cinnamon). Once more written by, for, and about queer Arab women. These rich narratives take place in Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and Syria respectively, giving readers a complex, close, and varied experience of same-sex desires and practices within Arab communities, families, spaces, and politics.

“It often comes as a surprise to Western and some Arab audiences that the majority of works about same-sex desires and practices between Arab women are not, as Orientalism would have us believe, originating in the West or in English,” says Shomali, who was named the 2017 Outstanding Faculty Ally at the Lavender Celebration, UMBC’s yearly event honoring LGBTQIA+ students, faculty, and staff. “They are works by Arab authors and artists, produced in Arabic, in Arab nations.”

A free and joyful queer future

In addition to texts, Shomali connected with filmakers, artists, and designers currently advancing perceptions and practices of gender, sexuality, and liberation from oppressive systems within Arab culture creating a joyful and thriving present and future in film, fashion, and illustration.

Maysaloun Hamoud’s 2016 narrative film Bar Bahar (In Between) tells the friendship of three Palestinian roommates living in occupied Palestine working through issues of cultural expectations, identity, desire, and freedom. Nöl Collective is a clothing production company and intersectional feminist and political fashion collective based in Ramallah, Palestine. It works with Palestinian women artisans to create clothes based on traditional methods as a platform to bring awareness to political, environmental, and intersectionality issues as shared on their website.

“The political reality for Palestinians is shaped by the military occupation which touches and shapes every element of our lives, including creativity. Isolated from one another geographically most of the artisans we are working with have never met and even need to work together digitally to bring garments to life, representing a creative endeavor which has triumphed over imposed borders.

Nöl Collective

Detroit’s own Maamoul Press is a small multidisciplinary art collective that supports the production and circulation of creative works in the genres of comics, printmaking, and book arts in the Arab diaspora.

“Ultimately, Bar Bahar, Nöl Collective, and Maamoul Press are geared toward a queer Arab future whose ethnic, sexual, and gender politics point toward collective liberation rather than community gatekeeping and social erasure,” says Shomali. “They do so by centering diverse voices, substantiating a future in which queer Arabs not only exist and experience pleasure, but whose existence, pleasures, and activists are essential to a sexually free future.”

“By positioning the work of diaspora artists alongside the work of artists living in our home countries, we seek to break down barriers that fragment our communities.

Maamoul Press

Shomali chose the word banat because it is void of the western, Orientalist, and hetero-patriarchal gaze that has defined queer Arab women into three stereotypes of Arab women’s religion, sexuality, and political beliefs. Between Banat is about all the spaces in between queer Arab women’s loving and living. Their past and future, visibility and invisibility, heterosexuality and queerness, empires and colonies, western and Arab.

“When I felt like it was impossible to write this book, I thought about my Palestinian ancestors and how I was bringing to bear a future we couldn’t have imagined,” says Shomali. “I believe in our joy and I believe our freedom is coming. I am grateful to them for teaching me that I am not alone.”