What if you could ask yourself a big question and then use your intuition to follow it wherever it led for as long as it took? It would take a certain kind of guts, right? But, with a willingness to get lost on a tangent, to joyfully put themselves in positions of not knowing, truly creative thinkers can find new ways of translating the world around them.

Enter the following: A dancer who makes beautiful movement from fish research. An information systems professor who turns poetry into wine. A data visualizer who draws connections while splattering paint. A mapper and sculptor of hip hop facts. A harnesser of color and language and culture.

This is the sort of magic that can happen when you’re open to interpretation.

On a molecular level, the push and pull of an ecosystem may feel too infinitesimal for humans to experience visually. A researcher can track the data in a spreadsheet as a series of characters and marks or explain it with the structure of a scientific article. Microscopes may capture stills or video of tiny worlds, but what about the emotional landscape of life in motion?

“I really am fascinated with the small things we cannot see that are so important,” says Ann Sofie Clemmensen, assistant professor of dance, who spent a year in residence at the Institute of Marine & Environmental Technology (IMET) next to Baltimore’s Inner Harbor working with scientists who study a variety of topics adjacent to aquaculture, environment, and sustainability.

Clemmensen began her residency by diving deeply into the research of the IMET scientists around her—learning about everything from rainbow trout viruses to the ecological wear and tear of red tides. As she built relationships with researchers, she found herself drawn into the details of their studies—and wondering how she might translate what she learned into something that might encourage viewers to learn more about their world.

“There’s a sort of unpacking of the language of that field. Because movement, while it’s not a spoken language, it is language,” she explains, ever the eager translator. “We have to understand the concept we are trying to embody in order for the physical embodiment to carry the meaning.”

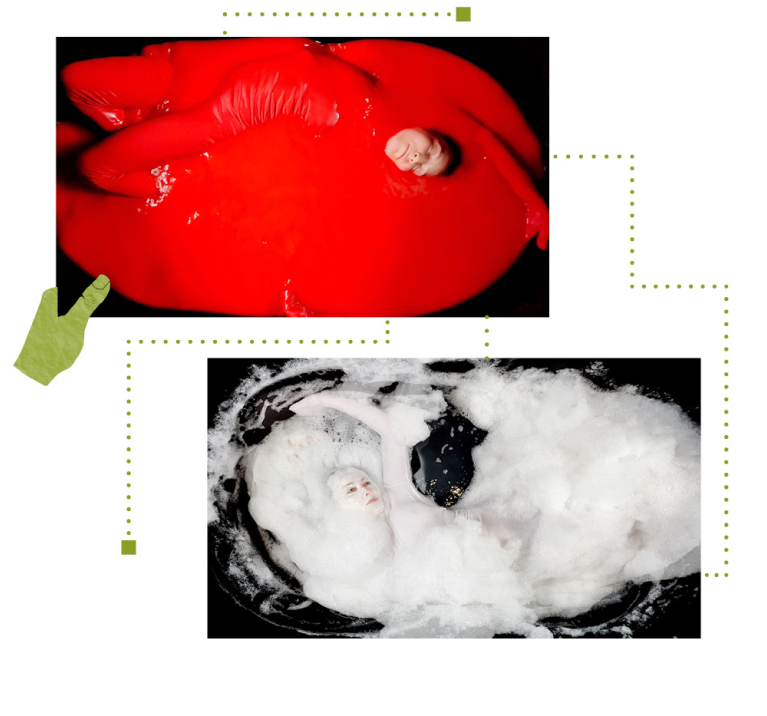

Working with student dancers, Clemmensen choreographed and filmed a series of movements and scenes meant to depict biological processes she learned about from her IMET counterparts. In one, students in masks represent the generic differences of virulent and avirulent strains of the VHSV rainbow trout virus. In another, dancer Michaela Emmerich ’24 (covered in clay powder) rolls in the dirt to show the effect of argonite in reducing levels of phosphorus in farming run-off.

While Clemmensen’s scenes of red tides, green biomass, and white, milky foams are objectively beautiful, don’t be fooled. Nature isn’t pretty, Clemmensen says. But taking a good close look can help us all understand our environment a bit better.

“For many doing art, dance, and data-driven research, it’s like looking at an abstract painting. If you don’t have a little key that can unveil or reveal some of those secrets, then it’s just chaos.”

Assistant professor Ann Sofie Clemmensen worked with

researchers at IMET to create a series of videos depicting

microscopic processes like red tides and battling

dinoflaggelates. Photos courtesy of Clemmensen.

Assistant professor Ann Sofie Clemmensen worked with

researchers at IMET to create a series of videos depicting

microscopic processes like red tides and battling

dinoflaggelates. Photos courtesy of Clemmensen.

A poem crosses time and space, building in meaning as it travels from person to person, from generation to generation. With each new reader, it becomes something new and specific—but also potentially loses something of itself along the way.

As a trained computer scientist, Foad Hamidi, assistant professor of information systems, is fascinated by the practical challenge of being able to retrieve information lost when data is duplicated—an inevitable fact of digital life. As a lifelong lover of Sufi poetry from his home country of Iran, he also can’t help but wonder how to preserve the heart of these precious words, even as circumstances—generations, distance, cultural leanings—might dilute or change them.

“There’s always some information loss” in data duplication, he explains. “However, a very interesting theorem in information theory also says that if you have a lot of replicas of the same code…you can recover the original message in the presence of errors that was in all these codes.”

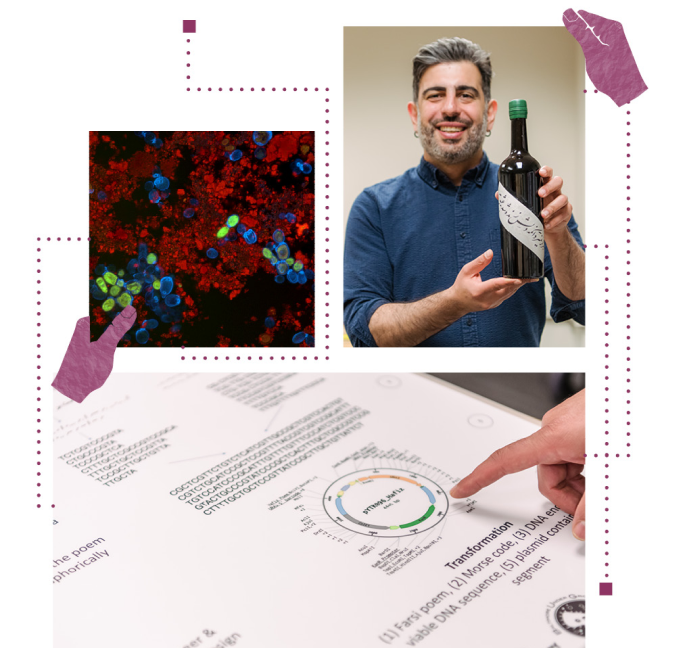

Information systems Professor Foad Hamidi has

translated a favorite childhood poem into DNA code,

wine, and more. Top image (magnified photo of yeast

cells with the modified DNA Hamidi made)

courtesy of Tagide deCarvalho.

Information systems Professor Foad Hamidi has

translated a favorite childhood poem into DNA code,

wine, and more. Top image (magnified photo of yeast

cells with the modified DNA Hamidi made)

courtesy of Tagide deCarvalho.

Years ago, Hamidi learned about a song that was encoded by Japanese musician Etsuko Yakushimaru using living bacteria as a sort of language, “and it really made me think of the possibilities of information and culture and data and encoding.” And so, at the start of the pandemic, he began exploring ways of translating the poetry of Hafiz, a 14th-century Persian poet, into new, living forms and of sharing the experience with others.

Hamidi’s bio-art-inspired creative inquiry led him first to interpret the poetry as code—DNA, to be precise—culled from the words themselves. He then created a “poetry-infused transgenic wine” using yeast modified with the DNA encoding of the poem. Craving community, he took the idea to other researchers in music, biology, imaging, and beyond to joyfully build further iterations of the chain. These efforts led to an Imaging Research Center (IRC) Faculty Research Fellowship (with Linda Dusman, professor of music), and today, he continues to explore new translations of the coded poem through music, cellular imagery, and even a cluster of mushrooms growing in Hamidi’s office.

With each new link in Hamidi’s poetic chain, the information is replicated and the “data” is one step closer to being saved through this fascinating theorem. In doing so, Hamidi also is able to bring together curious new friends who might not have had reason to collaborate otherwise.

Although Hamidi’s “translations” may seem outside the box, the practice of making a poem one’s own “has a long history,” he explains. “These poems are the DNA of my culture…so our architecture, our music, our visual arts, our cultural traditions, are very much impacted by poetry.”

In a far corner hangs an enormous painting of a brain, with bright blue lines, red arrows, and clips of phrases suggesting ideas in motion. In every direction above it, threads of red and blue crisscross the room anchoring one artwork to the next—a system of knit synapses representing not only 25 years of research but the artistic process that fuels it.

“What I try to do, above and beyond anything else, is show as transparently as possible what that process looks like,” says Lee Boot, director of UMBC’s Imaging Research Center (IRC), whose retrospective exhibit “Abstracts & Artifacts” showed at Baltimore’s Peale Museum earlier this spring.

For Boot, that means a room filled with numbers, images—some animated, many bursting with color—and the connective tissue of the personal paintings he created to process information and experiences related to the various subjects of his research.

“The work is immersive. I paint my brain out as a meditative, reflective process. And then that gets honed, and reshaped, and…out of that automatically comes new perspectives and new ways of framing problems.”

In his exhibit “Abstracts & Artifacts,” Lee Boot asks

viewers to consider new ways of solving problems.

“Almost like dreaming, making art with a question

in mind reveals meaning through metaphor. How

is it that metaphors seem to be both specific and

ambiguous—both personal and universal—at once?”

In his exhibit “Abstracts & Artifacts,” Lee Boot asks

viewers to consider new ways of solving problems.

“Almost like dreaming, making art with a question

in mind reveals meaning through metaphor. How

is it that metaphors seem to be both specific and

ambiguous—both personal and universal—at once?”

Boot lives to solve problems, and believes deeply in the power of combining artists’ ways of thinking with other disciplines to ask questions and find solutions in new ways. Over the years, the IRC has brought together multidisciplinary teams of artists, scientists, and social scientists from state and local agencies, foundations, and other organizations who are open to tackling everything from substance misuse to educational achievement gaps to the epidemiology of pandemics.

And while technology runs much of what the IRC builds, nothing is quite so essential to the heart of the work as one’s own intuition, says Boot. As a classically-trained painter, that means returning to the canvas and allowing his brush to take him in new directions—not to create something beautiful, per se, but to open himself to ideas accessible only through such a personal process.

With each stroke of the brush, and each new color, he pulls from the deepest reaches of experience, community, and understanding, creating a road map for what’s next.

“I’m not trying to make something pretty,” he says. “I am trying to understand how a set of issues sits in being, in my psyche, on the landscape of the world as I understand it. I’m trying to see what I cannot see.”

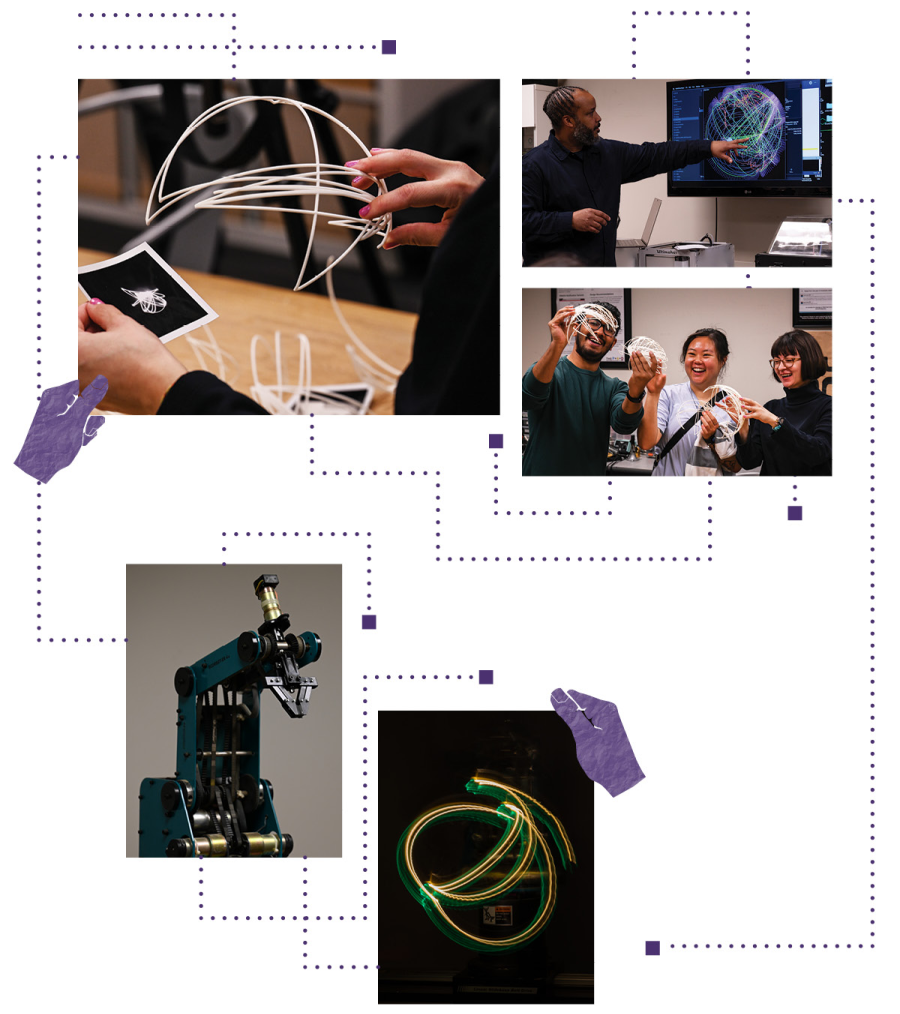

On the table sit three football-sized forms of light plastic. Each has been sculpted in a 3D printer using zigzag motions specifically programmed to mimic the map lit up behind them showing an orange globe splashed with green arcs. Dots on the screen represent locations mentioned in thousands of hip-hop and rap lyrics, as big as the oft-mentioned city of Atlanta and as hyperlocal as the intersection in front of a neighborhood convenience store.

A student gingerly picks up a gold-colored sculpture, and asks, “Is this Kendrick Lamar?” Tahir Hemphill, a faculty fellow, music aficionado, and self-described “creative technologist who works with art,” nods as a collective “oooh” makes its way around the room.

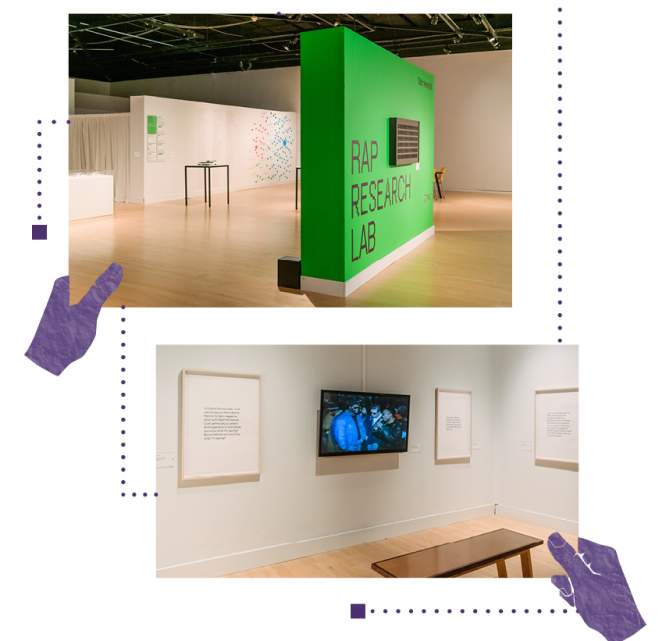

“It’s data sculpture, literally. It’s making things as real as possible,” says Hemphill, whose ever-evolving body of work, The Rap Research Lab, made its home at UMBC’s Center for Art, Design, and Visual Culture this spring. “This is what it feels like to touch a rapper’s rhymes.”

Located at the intersection of hip-hop and data visualization, and built as an interactive teaching space, the lab features the “Mapper’s Delight” tool that, using augmented and virtual reality, cross-references locations from thousands of rap song lyrics along with a variety of other art pieces that speak to Hemphill’s goal of finding “relationships and shapes in the data.”

Over the course of the semester, UMBC students helped Hemphill delve further into the data while middle schoolers from around the state visited the teaching lab with their classes to try their own hands at research using Hemphill’s lyrics database.

On this particular day, Hemphill demonstrates yet another incorporation of the geographic lyric data. In collaboration, Foad Hamidi helped Hemphill program a robotic arm, and by inserting a LED pen into the robot hand and filming movements at a long exposure, he’s able to make “light pen drawings” of the data, à la Pablo Picasso.

With the lights dimmed and the robot arm making ethereal data shapes before their eyes, Hemphill tinkers with his projected spreadsheet in real time. There are just so many threads to follow and infinite stories hidden within.

“My job is to draw them out—pun intended,” he laughs.

Tahir Hemphill, a faculty fellow, music aficionado, and

self-described “creative technologist who works with

art,” uses data visualization tools to reveal new levels

within hip-hop.

Tahir Hemphill, a faculty fellow, music aficionado, and

self-described “creative technologist who works with

art,” uses data visualization tools to reveal new levels

within hip-hop.

Read how artist Hadieh Shafie, M.F.A. ’04, channels the power of language and her childhood experiences in Iran into intricate and colorful pieces of art.