Having the sally port gates slam behind her after walking into the prison for the first time was a bit of a shock to Susan Beck ’74, French. Luckily, a friend was there to hold her hand as they adjusted to the tight space and waited for the next door to open. As Beck got her breathing under control, she joined her classmates in a clinical pastoral education class on the rest of the tour of the facility.

Beck, a former French teacher and a childbirth instructor, never envisioned her retirement as a career rebirth, but as she contemplated how she wanted to spend her time, she kept returning to her love of the church and wondered how she might serve. Prison ministry was the farthest idea from her mind, says Beck now. She imagined shepherding a congregation and ministering to families, but what that evolved into was a role as a community pastor, hosting weekly pub theology sessions and also stepping in as an interim pastor at different churches.

When her predecessor tapped her to think about taking over the spiritual leadership of The Community of St. Dysmas—a Lutheran ministry within the Maryland State Correctional System—Beck thought “no way” at first. But after Beck started volunteering with St. Dysmas, “It was pure gospel,” she says.

Serving an incarcerated congregation

These days Beck works out of a donated office space down the street from UMBC at the Salem Lutheran Church in Catonsville. Before heading to the correctional facilities in the evenings, Salem has set aside space for Beck to make copies, write her newsletter, and put up notes and cards from her congregants behind bars.

Beck at her formal installation ceremony, which took place at Salem Lutheran Church in Catonsville. Photo by William Beck.

Beck at her formal installation ceremony, which took place at Salem Lutheran Church in Catonsville. Photo by William Beck.

“Christianity is so focused on forgiveness of sins and God’s grace and God’s unconditional love, and that transforms people,” says Beck, who received her masters of divinity from Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg in 2010. “I do not seek to ever find out what their offenses are. That’s not important to me as their pastor, but sometimes they tell me. And as a mother and a grandmother, it’s really hard to hear—but when someone seeks God’s forgiveness and they get it, it changes their lives. It doesn’t change their circumstances. They’re still going to live out their sentence. They may never get out of prison, but everything’s different. That’s Jesus’ message and it was right there in the prison, and I absolutely loved it.”

Beck explains that while there are many larger prison ministries, St. Dysmas is one of the only places that provides a welcoming and affirming service for the LGBTQAI+ community within the Maryland prison system. “We very much welcome the questioners and the people who aren’t quite sure where they belong…. We welcome first and walk with people along their way, which is a very Lutheran thing to do.”

In post-canonical biblical literature, St. Dysmas is named as the criminal who dies next to a crucified Christ, asking to be remembered in the afterlife. “So our saint is a convicted criminal,” says Beck, “as was our Lord and Savior. Jesus died with a criminal record. How about that?”

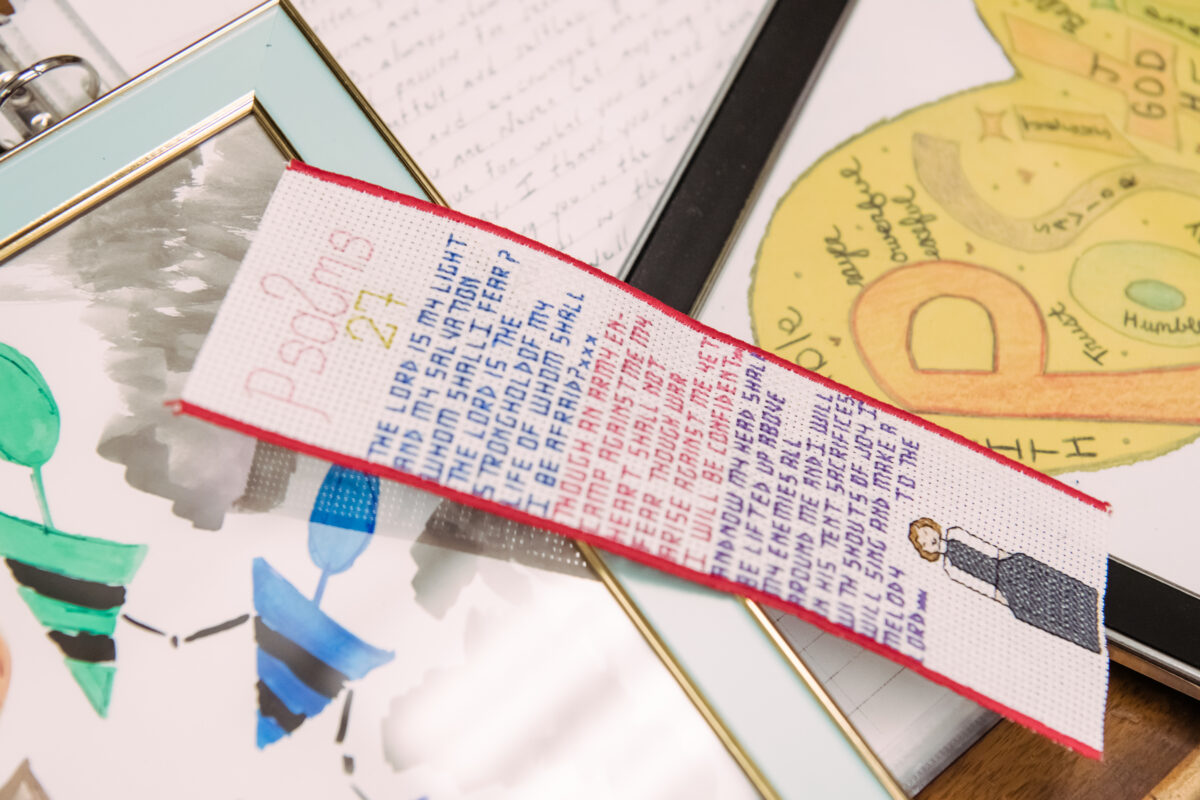

A collection of items made for Beck as gifts by her congregants.

A collection of items made for Beck as gifts by her congregants.

In January 2023, after nearly five years of doing this work, Beck was formally installed as the pastor to a congregation entirely behind bars but spread out over the Maryland state prison system. On Monday nights she’s in Hagerstown; on Wednesdays, Sykesville; and Saturdays in Jessup. Beck is accompanied by a rotating cadre of volunteers, who step up to make sure each facility has coverage for worship services and Bible studies.

Creating a sanctuary behind bars

What an average service looks like for Beck is after the sally port gates shut behind her and the next set of doors opens, she needs to successfully go through a metal detector in fewer than three tries. (“Don’t wear bras with underwires.”)

In a clear, plastic purse, she only brings with her items on an approved list from the Maryland Correctional Facilities: bread and a sealed container of grape juice for communion, devotional materials, different colored cloths for different liturgical seasons. Sometimes she needs other materials. “I did a baptism a couple of weeks ago, and I had to send many reminders to the administration that, ‘I need to bring in a plastic bowl. It’s just a plastic bowl.’”

If she successfully makes it through the metal detector, she is patted down by a female guard, and then escorted to the space her congregation will use to worship. Sometimes it is a room and sometimes it is a hallway. Usually members of the congregation will set up chairs and arrange the area for worship. Beck or another volunteer will play music (she has the paperwork cleared to bring her violin in), and they will create a sacred space within the prison walls.

Beck serves communion, offers a time for reflection, and shares a short sermon. “Over time, as they hear us preach and teach and talk—and the services are very interactive—those relationships build. And even though we’re informal and it’s not a cathedral, it’s not a sanctuary like you would imagine, I want to create a sanctuary for them.”

Shared humanity

Beck, who is 70 years old, says that this work she previously couldn’t have imagined for herself continues to energize her. “UMBC offered me an accessible path to education,” reflects Beck. “But you don’t ever stay on one path—you go off and expand it.”

When she goes to leave the prisons at night, her parishioners will tell her, “Watch out for the deer. They’re crazy this time. You’ll watch out for the deer?” And as the sally port gates shut behind Beck, with her now on the outside, she says, “I know on the other side of that door, there are gangs and there’s danger and there’s people yelling at them. But they said, ‘Watch out for the deer.’ That’s just so human.”