In a large room, around 30 participants sat in two semi-circles of foldable chairs facing a panel of people invested in Baltimore and connected to UMBC. Despite the perfect spring break weather, these UMBC students weren’t on vacation. Instead, they gathered around three blue coffee-stained rugs of different shades and sizes with brightly marked poster paper on the walls depicting the community standards like “Take space when you need it,” “Listen non-judgmentally,” and “Don’t be afraid to ask questions.” Pens move steadily across the pages of students’ decorated notebooks.

It was the first day of Alternative Spring Break (ASB), a week-long program hosted by the Center for Democracy and Civic Life and coordinated by Faith Davis ’22, sociology and biological sciences, the Center’s community civic engagement intern. “Our program is student-led, so it evolves and takes new forms every year,” explains Davis. “By staying in Baltimore, we are able to equip participants with the tools and knowledge to contribute to sustainable change regarding the social issue their group focuses on. We believe that students are capable contributors to a better world, and ASB orients them to become aware of that.”

“Alternative Spring Break is about opening the door to sustained engagement in Baltimore,” said David Hoffman, Ph.D. ’13, language, literacy, and culture (LLC), and Romy Hübler ’09, modern languages and linguistics, M.A. ’11, intercultural communications, Ph.D. ’15, LLC, director and associate director ofthe Center, respectively.“Participants learn about the systemic and human dimensions of issues affecting the city, make connections with people doing creative and important work, and discover opportunities to make their own meaningful contributions.”

Learning to ask good questions

This year ASB consisted of three student-led groups: Immigrant Health Equity, K-12 Education Equity, and Transformative Justice. The first session of the week: “Contextualizing Baltimore,” allowed for all of the students to engage with the content together. Campus and community leaders discussed the reality of Baltimore City as separate from the negative stereotypes that are sometimes associated with it.

“Baltimore has a very rich history… the persistence of the negative narratives are by design,” Eric Ford, director of the Choice Program shared. “When you hear stuff you should always question what people mean and who it’s coming from. Ask questions not just of people with the title, but also with the people who don’t.”

Throughout the week, UMBC students in each of the ASB groups would follow Ford’s exhortation and ask hard questions—of their community guides and also of themselves, ultimately using the week to begin building relationships with organizations focused on education, provision of services, and advocacy.

Approaching education critically

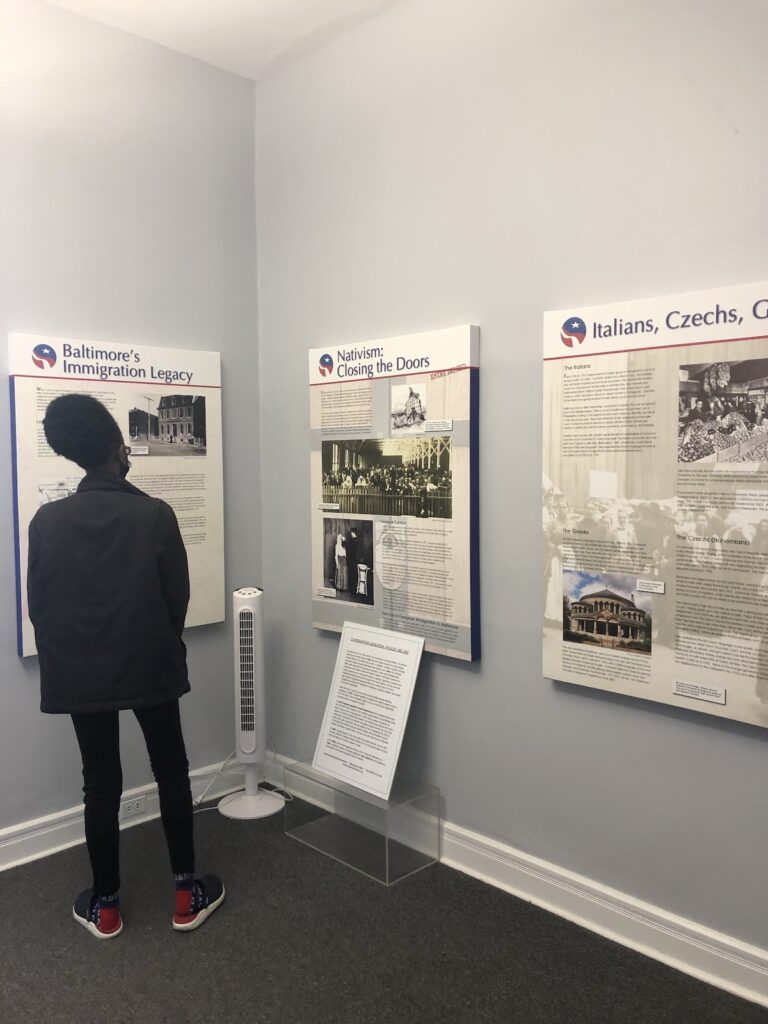

As Retrievers know, learning is a continuous process, and the Immigrant Health Equity group exemplified that by seeking more in-depth knowledge of the immigrant communities in Baltimore. They traveled to a small museum situated next to a beautiful little church to hear a speech about immigrant trends from the beginning of America to current times.

At the end of the lecture, Mokeira Nyakoe ’23, health administration and policy—one of the student leaders—shot her hand up, inspiring others to follow. Students raised critical questions about the information they were given and continued to interact with the docent as they queried for more in-depth information on Black immigrant experiences and the historical context and impact on current immigrant restrictions. After the facilitation ended, students actively reflected on the history they heard—and didn’t hear—by traveling to different parts of Baltimore with immigrant communities and supporting local businesses.

New ways to dream

Learning in many ways is a foundation for bringing about the changes you want to see. The Transformative Justice group went to meet with H.O.P.E (Helping Oppressed People Excel) an organization dedicated to providing relief and advocacy for previously incarcerated individuals.

Students walk to Emmanuel Episcopal Church where H.O.P.E operates.

Students walk to Emmanuel Episcopal Church where H.O.P.E operates.

Antoin Quarles, the founder of H.O.P.E, met with the students in midtown Baltimore, guiding them through an ornate building that reached for the heavens. Inside, the walls held both the solemn faces of long-dead church leaders and colorful Black Lives Matter flyers with pictures of Quarles standing side-by-side with Maryland leaders.

Quarles started the session by sharing his past. What started as a heartbreaking story—the result of generational trauma and systemic racism which had transformed the streets of Baltimore into “a battleground” and left Quarles in prison multiple times—eventually evolved into a story of direct advocacy, when Quarles founded H.O.P.E. “Whether it be finding housing, auto insurance, or a job, prison puts a noose around your neck which you can never escape from,” Quarles relayed.

While also assisting with resources like expungements, clothes, and backpacks, the organization’s main focus is advocacy. Spearheaded by Quarles, the organization fights for changes in housing, insurance, job market, and hospitals relating to the treatment of formerly incarcerated individuals. “Before, I wouldn’t ask myself, ‘Did I like prison? Did I consider [going to prison] normal? Was I scared?’ Those were questions I didn’t ask myself,” says Quarles. “But now, I would lose my mind because of the freedom I have learned to have for myself. Before, I felt comfortable living terribly.” Quarles sees it as his life’s work to support other released folks in walking down a different path.

As UMBC students listened to Quarles’ overview of what H.O.P.E has accomplished, ASB student leader Wendy Zhang ’23, psychology and economics, immediately inquired on how students could get more involved. “The way you dream is determined by what you are exposed to,” reflected Shaniah Reece ’23, information systems, as the students sat arranged in a semicircle around Quarles.

A need-based community approach

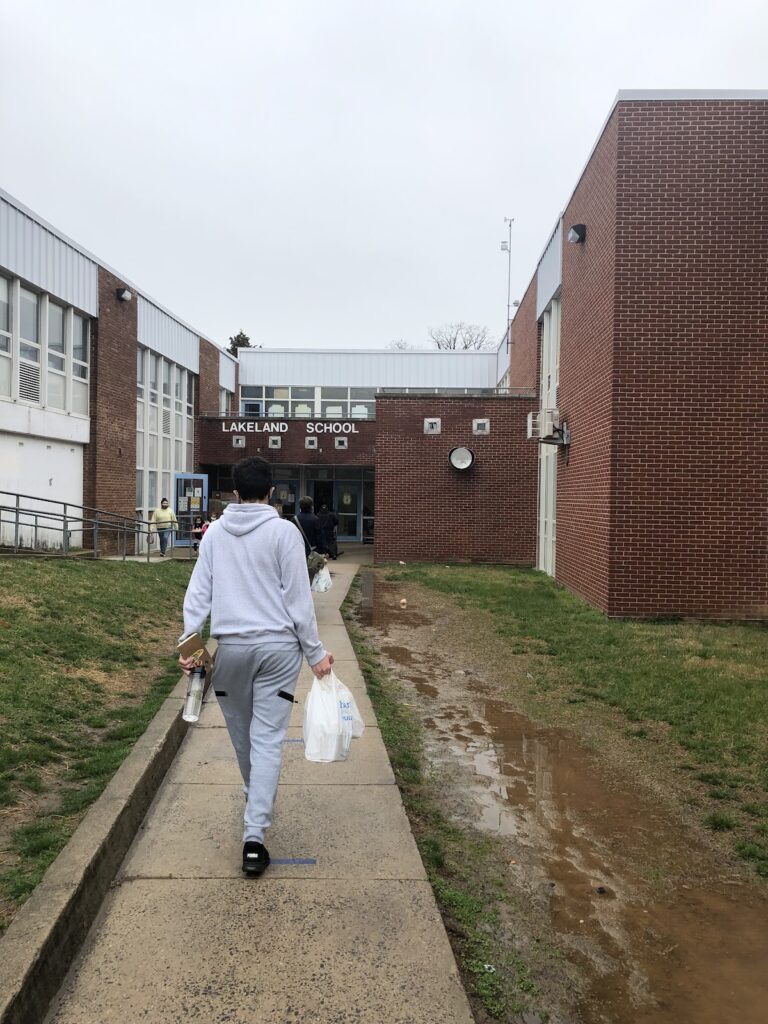

Meanwhile, the K-12 Educational Equity group toured Lakeland Elementary and Middle School. Colorful artwork decorated almost every inch of the school and the students conversed freely in Spanish and English. The school was described by the ASB students as a “happy and inviting” place.

Ramona Dowdell, the community school coordinator, explained the importance of a community school. Lakeland Elementary and Middle is interwoven with the surrounding neighborhoods, which largely are home to an underserved Central American immigrant population. On top of the academic work that a school usually does, Lakeland—in partnership with UMBC and other organizations—also provides bilingual education, a food pantry, communal baby showers, college advising, giveaways of backpacks, uniforms, and more. Because the school is connected to the parents and guardians of their students in multiple ways, Lakeland can provide programs and resources based on their unique needs.

ASB students tour Lakeland.

ASB students tour Lakeland.

During the tour, ASB participants walked past the MedStar mobile health center to unload a van full of grocery bags to a table set up right outside the school, where people from the community could grab what they needed. UMBC students saw the patch of dirt that come spring would transform into a garden, a soundproof studio where kids could record songs, and space for residents of the area to do their laundry.

Throughout their time there, students were warmly welcomed and given more information from the principal, Dowdell, and Brian Francoise, project director of Lakeland Community and the STEAM Center, one of the many members of UMBC tied to the community of Lakeland.

While reflecting on the group’s experience, Karen Griffin ’23, biology, began to ask more questions like, “Why is there not a push to have more community schools around Baltimore? What would my childhood, as someone who grew up low-income in Baltimore City, have looked like if my neighborhood had a community school?”

Investing in the communities around you

ASB participants, leaders, and staff from the Center for Democracy and Civic Life pose together at the end of the week.

ASB participants, leaders, and staff from the Center for Democracy and Civic Life pose together at the end of the week.

UMBC’s 2022 ASB took the first steps of building and maintaining long-term relationships with Baltimore organizations and deconstructing the idea of the city that often finds its way to the front pages. Together, participants unpacked ways to build trust with the respective communities their groups worked with, while not assuming what those needs are.

“The idea of an ‘Alternative Spring Break’ on college campuses has been around since the 1980s and was meant to provide students with a meaningful alternative to going to the beach all week” explains Davis, the student organizer. “The idea has since been commercialized, and many schools travel to a location, hours away, do service with an organization, and then return to their home campus. The ASB program at UMBC is unique because the goal is not to find something to fill your spring break but to use your spring break as an introduction to how meaningful change is made in Baltimore City.”

*****

Header image provided by the Center for Democracy and Civic Life.

All other photos by Charis Lawson ’20.