From cooking and cleaning to fixing your car, understanding chemistry can enlighten all aspects of life. That’s just one reason why Dean William R. LaCourse still loves sharing the joy of his favorite subject in front of a classroom.

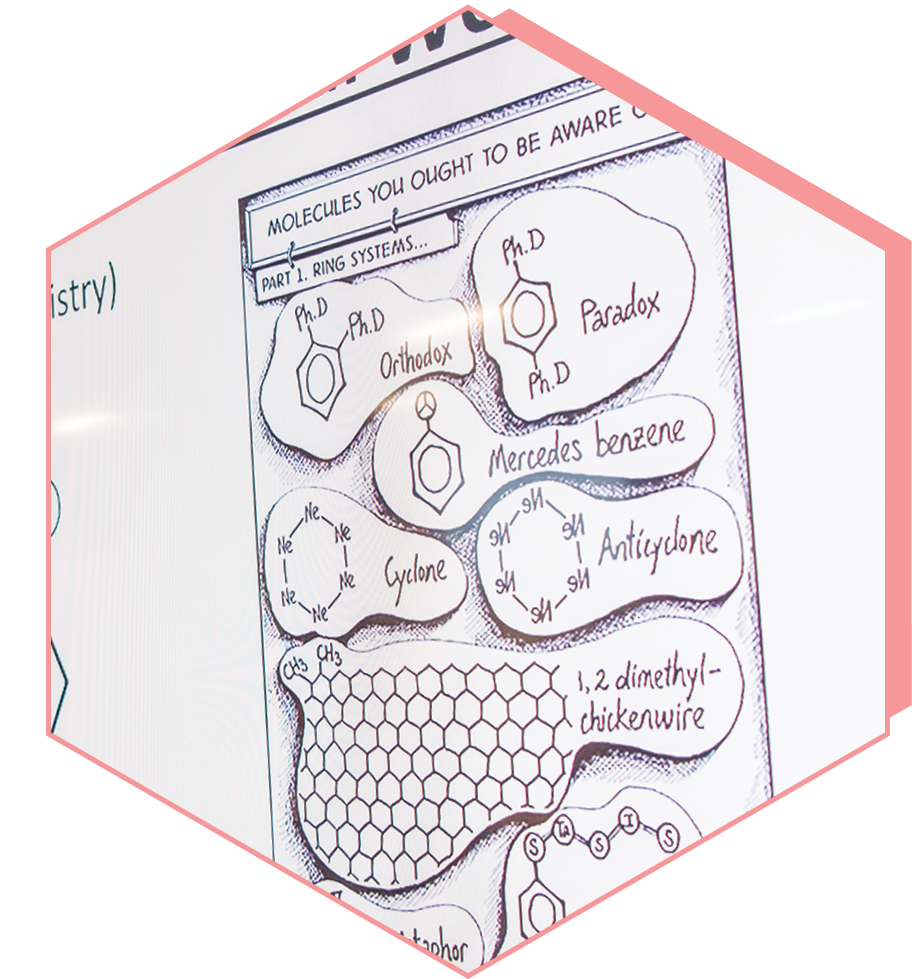

It’s not every institution where you can take a class taught by the dean— especially a 100-level course. It’s even less likely to find that dean sprinkling his weekly lectures with silly chemistry jokes and cultural references. But William R. LaCourse, dean of the College of Natural and Mathematical Sciences (CNMS) since 2011, does exactly that, co-teaching CHEM 100: The Chemical World to non-chemistry majors with Caitlin Kowalewski, assistant director of undergraduate initiatives in CNMS. Every Tuesday afternoon this spring, LaCourse taught his students how chemistry influences their lives.

The jokes and digressions are designed to keep a complex topic like chemistry light and relatable—even fun. After all, LaCourse tells his students one day in March, “This is not a course that’s supposed to stress you out. It’s an empowering course. At the end, you’re gonna know so much more about chemistry.”

Throughout the class LaCourse affectionately refers to as “the egg lecture,” for example, he teaches the students how best to make hard- and soft-boiled, fried, and baked eggs and exactly why based on the chemistry involved, with the occasional digression. The Lilliputians from Gulliver’s Travels, for example, make an appearance— apparently they went to war over which end of a soft-boiled egg to open. He also takes a moment to share a favorite recipe his wife makes—showing the students he’s more than a university administrator.

After the short lecture, the students answer discussion questions in groups, coming up with a list of compounds important for cooking, such as baking powder and gelatin, and their roles.

“CHEM 100 is all about empowerment,” LaCourse says. “Understanding how the chemical world affects you gives you more control over your life.” For example, you can avoid trendy health hacks that are actually bad for you, he explains. Understanding chemistry can even help you be more self-sufficient. You may be able to “fix your car, cook better meals, or take stains out of your clothing,” LaCourse says.

Students in the course appreciate that LaCourse makes the content relatable. “I don’t think I’ve ever had a science class before that connects to our daily lives in a way I can understand it,” says Keli Amoako ’25, political science. “He makes you aware of the chemistry in everyday life. I think everybody should have to take a class like this,” adds Moroti Oyeyemi ’25, information systems. There is something for everyone. “I have a great love of baking,” says Meghan Seerey ’23, visual arts, “and he connects the class to the culinary arts.”

For their final projects, students had complete freedom to demonstrate how chemistry affects their lives. Some created “day-in-the-life” presentations, explaining the chemistry in activities like brushing their teeth or doing laundry. Others focused on a particular interest, like skin care, fashion, or scuba diving. One student filmed a baking video, and another designed a brochure explaining how to improve one’s garden through soil chemistry. There were podcasts, poems, and even a musical composition in the key of C sharp. (The musical notation for C sharp, C#, looks like CH, representing carbon and hydrogen, two key elements for life.)

Connected to his roots

For LaCourse, teaching CHEM 100 follows naturally from his values. Even with the added responsibilities of a dean, after also serving as chair of the chemistry and biochemistry department for four years, and a member of the department for 15 years before that, “I still have graduate students and I still teach, because that’s the reason I came here in the first place,” LaCourse says. “I think if you move too far away from those roots that you’ll lose the ability to understand and to be empathetic with those who teach, with those who do research, and the issues that they encounter.”

Never has this been truer than over the last two years, as the COVID-19 pandemic forced administrators to make decisions about whether to shift classes online and other changes to the education experience. In Fall 2020 and Spring 2021, LaCourse and Kowalewski taught CHEM 100 fully online, in part to be in solidarity with the rest of the college’s faculty. “All the challenges with technology, grading, and keeping people’s interest…I could understand what the faculty were going through,” LaCourse remembers.

A non-traditional path

In addition to staying connected with the needs of faculty, LaCourse calls on his own experience to explain why he pursued the deanship and why he works so hard to make sure the college is serving all UMBC students well. He starts to talk about when he became department chair, then pauses.

“Actually, I’m gonna go back even faaather,” he says, revealing the Boston accent that still shows up now and then, despite living in the Baltimore area for decades. “I took a very non-traditional pathway to get where I am.”

He goes on to describe a series of experiences—starting out at a technical college, then pursuing a four-year degree at multiple institutions while working full-time, and a graduate education full of “naïve decisions” due in large part to a lack of guidance and support.

All that is what drove him to pursue leadership. It’s one thing to teach a course that shows students from all backgrounds why chemistry matters—and hopefully improve their lives in the process. It’s another to make changes at the department level, and yet another to be able to lead the college. LaCourse says his motto is “There’s always a better way,” similar to one of President Freeman Hrabowski’s sayings that has been adopted by many on campus: “Success is never final.”

“The world changes,” LaCourse says, “and most things will have to evolve to keep up.”

Discovery Learning

When LaCourse started as chair, he felt as if there were too many students failing introductor y chemistr y courses. He believed there was a better way—that the introductory chemistry curriculum needed to evolve. As a result, after a collaborative pilot program, introductory chemistry courses added a weekly, team-based, problem-solving session to the lecture component in 2005. These sessions are still a cornerstone of the chemistry curriculum today. The magic happens in the Chemistry Discovery Center (CDC), and LaCourse calls the technique “discovery learning.”

“Chem Discovery was a different way to do it. The vision was to bring students from a passive to an engaged format, to give them the opportunity to discover,” he says. “People love to discover things, to plant new flags.”

Research faculty get to experience that on a regular basis, LaCourse notes.

“Why don’t we give our students the opportunity to discover knowledge?” he says. “Because when you discover it, you own it—and we know that ownership is important for learning.”

After the Chemistry Discovery Center’s introduction, the fail rate in intro to chemistry dropped by half. The CDC plus a shift among UMBC faculty away from the concept of “weed out” courses has led to continued success, including increased retention and attendance.

Creating opportunities for all

Chemistry Discovery was just the beginning. LaCourse has spent nearly two decades working with colleagues across the college and at community colleges in the region to create more opportunities for students through a number of initiatives that supply the support and structure students need to succeed.

UMBC has proven again and again that relatively small, cohort-based scholars programs that generate a sense of community and offer intensive advising can significantly increase student persistence and success rates in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math). LaCourse isn’t satisfied with that, though—he wants to see more students get that high-touch experience.

“The whole purpose is to give opportunity and a unique education experience to every student that UMBC lets in,” LaCourse says. “The focus is on what we need to do to make that possible.”

Scaling up

The most comprehensive manifestation of this goal is STEM BUILD, a 10-year, National Institutes of Health-funded initiative at 10 universities to diversify the biomedical sciences workforce. At UMBC, the initiative’s motto is, “500, not 50.” That’s 500 students. “Can we do 500, not 50? Can we make things scalable?” LaCourse asks. “Can we take the pieces of community and intensive advising, and make it so many more people benefit from it?”

The goal of STEM BUILD at UMBC is to identify the most effective practices that support student success and find ways to implement them at scale. Perhaps most important, the college is working hard to weave the most effective elements into regular operations so that when the grant funding sunsets in 2023, students will continue to benefit.

STEM BUILD programming includes group research experiences, a summer bridge that teaches laboratory skills and experimental design, and training in communications and research ethics. Advising, community meetings and socials, living on campus in the STEM Living Learning Community, and a rich culture of staff and faculty support are key community-building elements.

STEM BUILD also spawned an Active Learning, Inquiry Teaching (ALIT) certificate through UMBC’s Faculty Development Center. ALIT has helped faculty transition their courses to more engaged formats, such as team-based problem-solving, rather than lectures. Spaces like the CNMS Active Science Teaching and Learning Environment, opened in 2010, facilitate this transition. CASTLE has round tables rather than desks, and since fall 2019, the new Interdisciplinary Life Sciences Building has offered similar classroom environments, plus features like mobile whiteboards. Originally, ALIT was intended only for faculty directly involved in STEM BUILD activities, but has since been expanded to any interested faculty—an example of the ripple effect of initiatives such as STEM BUILD.

Leading the change

LaCourse has also led efforts to capitalize on UMBC’s location in one of the top biotech clusters in the country. After hiring Annica Wayman ’99, M6, mechanical engineering, as associate dean of Shady Grove affairs in CNMS, degree options for UMBC STEM students at the Universities at Shady Grove have grown. “She has a passion for students and helping them be successful,” LaCourse says.

Wayman came back to UMBC from a successful career in international development at USAID specifically to lead the new Translational Life Science Technology (TLST) bachelor’s degree program, which prepares students for immediate, in-demand careers in biotech. “The relevance, innovative nature, and health-related impact of the TLST program is what attracted me back to UMBC as associate dean, and the many students who come into the program,” she says.

LaCourse’s leadership, in conjunction with community college partners, was crucial to bringing it to life, Wayman adds. “Bill’s educational start in community college and work in the private sector before coming to academia made him the perfect visionary for developing a new bachelor’s degree in biotechnology at UMBC.”

And it’s working. TLST grads like Titina Sirak ’20 and Charmaine Hipolito ’20 are already finding success in the regional biotech market, leaving the program with several job offers for biotech positions in hand.

LaCourse also knows that for students to succeed, faculty need to feel supported and be representative of the student body. The ADVANCE program, for example, has increased the number of women faculty in STEM by 180% since 2003. And now, the Pre-professoriate Fellowship program encourages faculty members committed to supporting diversity and inclusion to apply. The goal is for participants to convert to assistant professors at UMBC.

While persistence and success in STEM majors has significantly increased over the last two decades, “How many more successful students could there be if they could see more people like themselves, who they can relate to better?” LaCourse asks.

Doing right by students

Given his own challenges navigating higher education, supporting success for all students, enabling discovery, and encouraging ownership of their education is deeply embedded in LaCourse’s psyche.

One of his current graduate students in chemistry and biochemistry, Amanda Belunis, confirms this. “Dr. LaCourse always says that he is just a guide, and he wants us to be actively engaged in our own education and learn lessons. He pushes us all to reach our full potential and consistently offers constructive feedback and encouragement, usually paired with a funny anecdote or joke,” she says. “I feel confident that when I finish, I will be leaving the program as an independent critical thinker ready to tackle any problem, and I owe a lot of that to him.”

While some students may be likely to succeed regardless of the support available or not, for others, the right environment can make all the difference.

“When people come in, if you give them the feeling that they belong, and that they can do it, and you give them the help that they need, many, many more will succeed,” LaCourse says. This sentiment applies to faculty, too. Both students and faculty “put their future in the hands of the institution, that we’ll do right by them,” LaCourse says.

Nowhere like UMBC

Through his work with individual students in his laboratory, teaching undergraduates, and securing funding for projects that affect many more students, he’s doing his best to make sure the institution deserves its community members’ trust by creating opportunities and offering support.

“Opportunities are what life is all about,” LaCourse says. “It’s up to an individual to take advantage of them, but we have to put those opportunities in front of people and make people believe that they can take advantage of them.” Through programs like STEM BUILD, TLST, transfer student support programs, and more, “that’s what we train our students to believe—that they belong, that they could do the job, that that opportunity is theirs as much as anybody else’s,” no matter their background.

As a non-traditional candidate for a leadership role in academia, LaCourse also appreciates the opportunities he’s been given to make a difference at UMBC—the chances people took on him and his ideas, which sometimes involved creative new methods. Another pause. And then, “Of course I can’t know—as a scientist, I understand there’s no control group for my life,” he says. “But I don’t think I’d be where I am at any other place than UMBC.”

He’s taken it as his mission to pass on those opportunities to UMBC students—they’re why he’s here, after all. As a leader first in chemistry, and now in CNMS as a whole, he’s worked to “break down silos, and work under umbrellas,” as he says, to make changes that do the greatest good.

“You need to understand what everybody’s going through, and what they’re up against,” he says. “That way you can work together better in the long run—and again, we’re all working for the same purpose.”

Vision of what could be

The significant, positive change that has occurred on his watch is already impressive, and the trajectory is still going in the right direction. More students are succeeding in STEM at UMBC. Students who demonstrate high potential, but may not be at the top of their class or have much experience when they arrive at UMBC, are getting the resources they need and finding their way. Faculty and staff are committed to supporting all of them.

Although he’s not retiring yet, LaCourse has decades of experience at UMBC to reflect on. When asked about what a normal day might look like, after mentioning writing grant proposals, dealing with crises, attending leadership meetings, and, of course, teaching CHEM 100, he pauses again, waxing philosophical.

“A day in the life…” he ponders. “It’s really a lifetime, guided by principles and experiences from my own life. So every decision, every action, draws upon everything in the past, and the vision of what could be.”

Who knows what may come next.