For Christopher Tong, discovering clues hidden in texts documenting history’s most devastating floods isn’t just about the promise of making social, cultural, and political change. It’s also a personal journey inspired by generations of his own family.

In July of 2021, the city of Zhengzhou, China, had more than seven inches of rain in one hour, flooding subway train cars filled with commuters and forcing hundreds of thousands to evacuate.

Around this time Christopher K. Tong, an assistant professor of modern languages, linguistics, and intercultural communication, was surrounded by materials he had collected during his trip to the People’s Republic of China at the Hubei Provincial Archive in Wuhan and from the No. 2 Historical Archive in Nanjing, the national repository for Republican-era government documents. He was translating and analyzing historical, government, and personal documents regarding two major environmental disasters in China during the 1930s: the Yangzi River and Yellow River floods.

Nearly a century ago, the communities surrounding the third- and sixth-longest river systems in the world experienced the most severe flooding in modern China’s history, inundating thousands of miles of land, killing millions of people, and leading to extensive disease and famine.

Witnessing the coverage of the Zhengzhou flood, and watching the past and present intersect, was an extraordinary moment for Tong. Live, minute-by-minute social media posts gave insight into the catastrophic experience. By contrast, the floods from the 1930s did not have such personal coverage. First-person accounts tended to be handwritten letters and only some reached audiences beyond their villages, allowing for a select few, in cities far away from the areas most impacted, to understand what was happening on the ground.

“The Zhengzhou floods confirmed for me how important environmental humanities research is and how this scholarship sheds light on society and politics,” says Tong, who compares the impact of the floods to the impact the Dust Bowl of America’s Great Depression had on American society and politics. This deep research into the political—and personal—nature of environmental disasters like these has won Tong recognition among humanities scholars, social scientists, and policy analysts alike.

The Henry Luce Foundation and the American Council of Learned Societies recently awarded Tong one of 11 prestigious Early Career Fellowships in China Studies, providing funding for an academic year of research, writing, and curriculum development to help meet the needs of China studies in the 21st century. Tong will use this time and rich material to write his book on ecological consciousness and political representation in modern China.

“One of the goals of my book is to offer readers resources to ‘think with China’ on shared concerns such as ecological crises, human rights, and animal advocacy,” says Tong. “I see my work as contributing to cultural diplomacy and what people in the policy world call ‘China literacy.’”

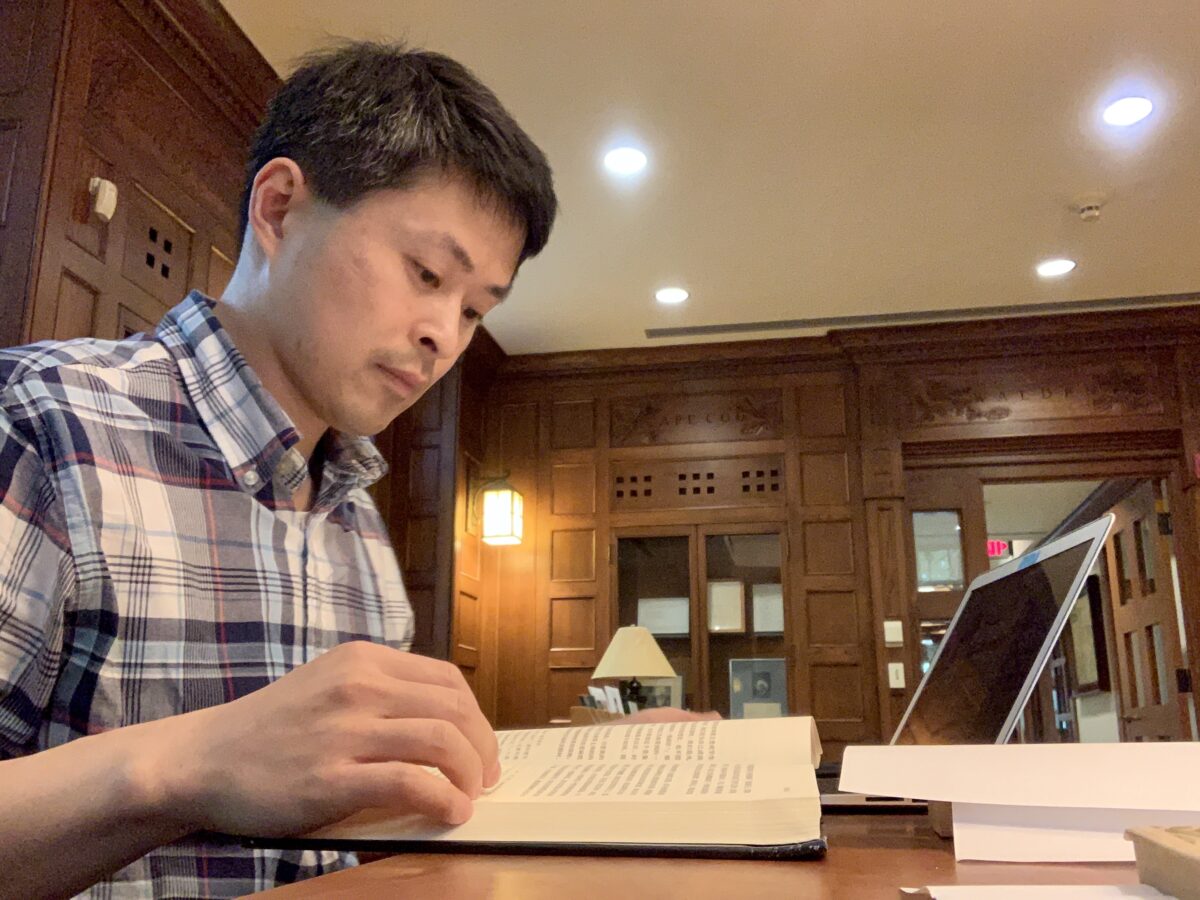

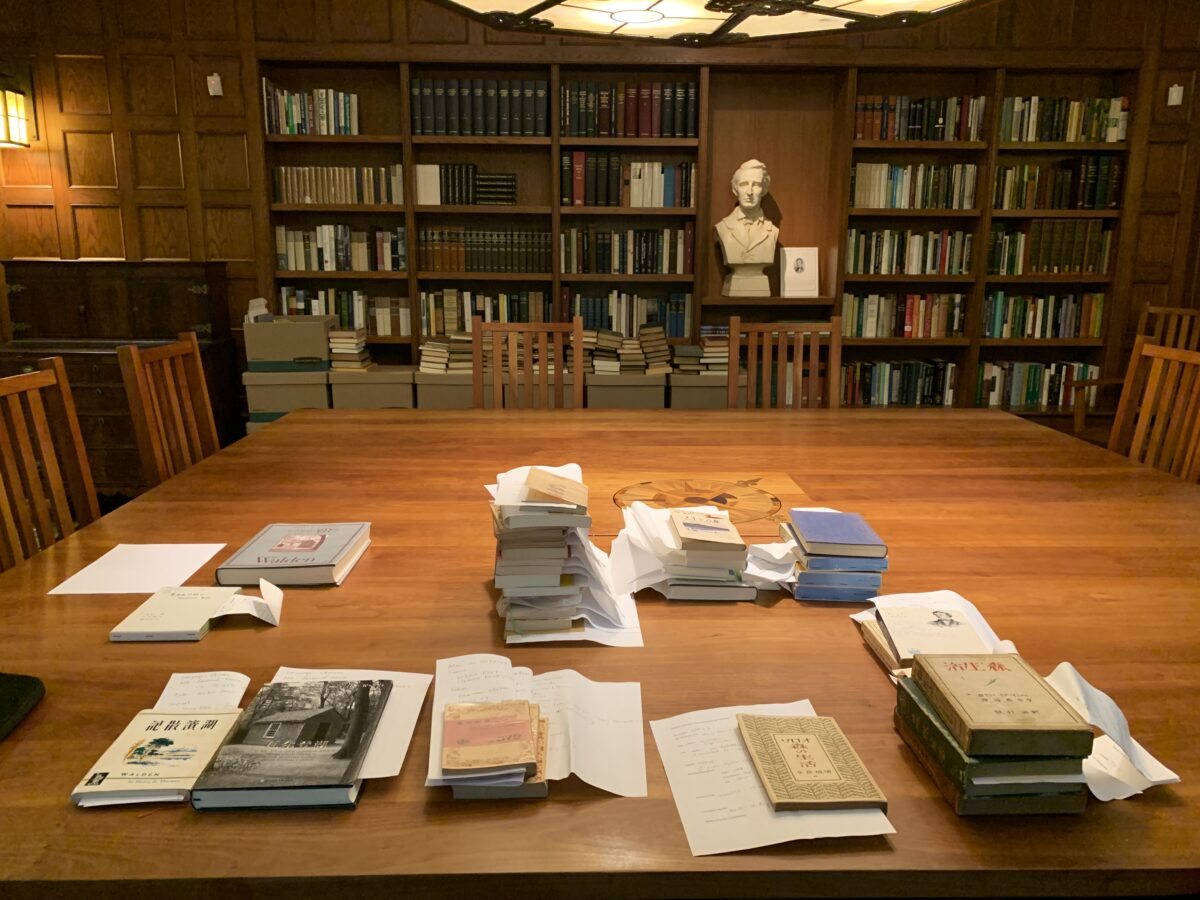

In September 2021, Tong spent two days examining, scanning, and taking notes on a number of Asian translations at the Thoreau Institute. Images courtesy of Tong.

In September 2021, Tong spent two days examining, scanning, and taking notes on a number of Asian translations at the Thoreau Institute. Images courtesy of Tong.

Silent all these years

Historical and literary narratives of the Yangzi River and Yellow River floods tend to shift between focusing on facts and offering a political party’s explanation. The events are inevitably understood within the larger framework of building a national identity, especially the revolutionary history of the People’s Republic of China.

“Official narratives generally serve to build national unity, but there are always gaps and discrepancies in these narratives. It’s about whose voices are missing in the official narratives and why,” says Tong. “Unfortunately, people forget these voices over time, and my project is to recover them.

Wanting to delve into the archives on the floods to see what histories emerged, Tong first had to secure access to the archives. With access granted and the assistance of a Fulbright grant and Nanjing University, between 2018 and 2019 Tong spent 10 months in China analyzing thousands of documents written in classical and modern Chinese. In the archives, amongst letters written by survivors, correspondence between county officials and provincial and central governments lists of survivors at refugee camps, maps, logistical documents, and photos never before studied, was one of many untold stories:

“There are those who try to rescue their parents, but die in the water…There are those who hold their wives and children by the hand, but end up drowning together…[and] families that manage to escape on a single raft, but sink in the middle of the current.”

This excerpt of a rare petition letter written by a village representative was in the archives and mirrored accounts throughout the archives that spoke of death and survival. These voices, silent for decades, were not a story of revolutionary action as many histories of modern China would imply. What Tong unearthed bears witness to the lived experience of rural communities focused on repairing and managing loss. They sought help from government officials, relief workers, each other, and were more civically engaged than previously thought.

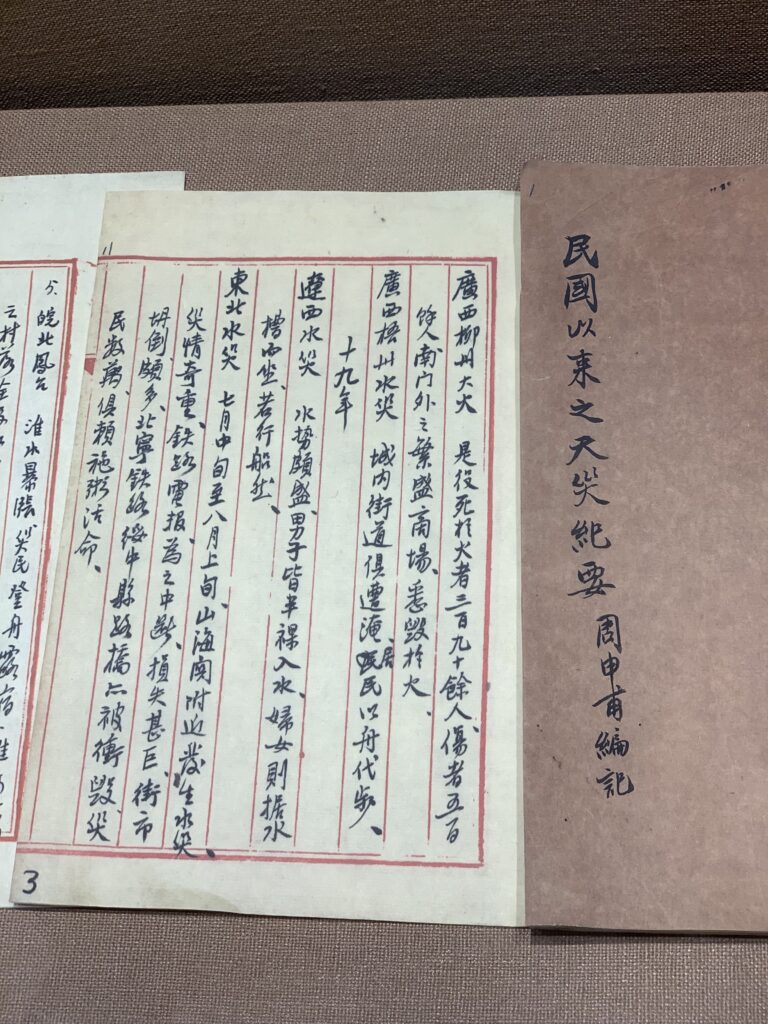

An archival document listing major environmental disasters in Republican China. Image courtesy of Tong.

An archival document listing major environmental disasters in Republican China. Image courtesy of Tong.

“Sometimes these efforts are not given enough consideration in disaster narratives and national histories,” says Tong. “But I believe them to be important as building blocks of proto-democratic practices.” He hopes it will inspire the reconceptualization of Chinese literature and history in the early 20th century.

Kirk Denton, professor emeritus of Chinese literature at the Ohio State University and a mentor to Tong through UMBC’s Eminent Scholar Mentoring Program, gave Tong important feedback based on his own research on the representation of historical memory in Chinese and Taiwanese museums. Over the years, Denton has witnessed the evolution of Tong’s work.

“I was heartened to see a young man mature into such an accomplished scholar,” says Denton, who notes that Tong’s work “is at the forefront of the environmental humanities.”

Jessica Berman, professor of English and director of UMBC’s Dresher Center for the Humanities, says that as a scholar of comparative literature, “Christopher uses the core methods of textual analysis, critical theory, and intellectual history to bring out the ramifications of cross-cultural environmental thinking between China and the U.S. in the early 20th century.”

“The climate crisis is often portrayed as something serious that happens over time, like global warming,” says Tong. “However, with the Dust Bowl in the U. S. and floods in China, these disasters were fast and extreme and often contributed to immediate shifts in public sentiment and the government’s capacity to govern.”

Tong stands in front of Nanjing University’s auditorium at the downtown campus, which features the fusion of traditional Chinese architectural elements and modern Western construction methods. Image courtesy of Tong.

Tong stands in front of Nanjing University’s auditorium at the downtown campus, which features the fusion of traditional Chinese architectural elements and modern Western construction methods. Image courtesy of Tong.

Windows to the past

For Tong, the interconnectedness of his work is both personal and professional. His interest in 20th‑century China and Hong Kong stems from his maternal grandmother’s stories about her life in mainland China in the early 20th century.

“My maternal grandmother and her sibling were artists. She went to an art academy in China briefly during W WII and was the director of a clothing company in Hong Kong after the war. One of her sisters was a film star in Hong Kong who acted opposite a young Bruce Lee in the film Thunderstorm in 1957,” he says.

He remembers learning about his great‑great‑grandfather, Jiang Kong yin, a government official and well‑respected member of the gentry during the Qing dynasty, the last imperial dynasty in China. Jiang helped with the transition from the Qing dynasty to the Republic of China (ROC). Tong’s maternal grandfather learned English early because he was from one of the founding families whose fortune was tied to British Hong Kong. This was especially useful during WWII when he worked for Allied forces in southwestern China with Chinese aviators and the Flying Tigers, U. S. volunteer aviators who fought against Japan.

Left: Tong visited Dr. Sun Yat-sen’s Mausoleum on Nanjing’s Purple Mountain and wore his Fulbright shirt as a way to commemorate the US-China connection and his Fulbright experience in China. Right: The Fulbright program in China was cut short in 2020 by the pandemic and subsequently canceled, making Tong’s visit the last full year of Fulbright exchange in the People’s Republic of China. Images courtesy of Tong.

Left: Tong visited Dr. Sun Yat-sen’s Mausoleum on Nanjing’s Purple Mountain and wore his Fulbright shirt as a way to commemorate the US-China connection and his Fulbright experience in China. Right: The Fulbright program in China was cut short in 2020 by the pandemic and subsequently canceled, making Tong’s visit the last full year of Fulbright exchange in the People’s Republic of China. Images courtesy of Tong.

Tong also listened to the stories of his paternal grandfather who worked for an American company in Hong Kong after WWII. His paternal grandmother came from a peasant family and joined her siblings in the U.S. Her siblings ran a Chinese restaurant in Bakersfield, California. This side of Tong’s family eventually moved to the San Francisco Bay Area where his uncles would later work for the U. S. military. California has been home to most of Tong’s family since the late 1960s.

“I’m proud that my research not only broadens scholarship in the humanities,” shares Tong, “but it is also a way to maintain my connection to my family history and imagine what it was like for them to live through those periods.”

Tong stands below two plaques on the side of the former Hankow Customs House in Wuhan, China. The plaques are placed at the high-water marks of the 1931 floods (lower) and 1954 floods (higher). Image courtesy of Tong.

Tong stands below two plaques on the side of the former Hankow Customs House in Wuhan, China. The plaques are placed at the high-water marks of the 1931 floods (lower) and 1954 floods (higher). Image courtesy of Tong.

Mirrors

Tong’s work also holds space for voices missing in the humanities and the environmental movement. “Ecological thought draws heavily on European and North American traditions. Non-Western cultures are often viewed as derivative or marginal,” explains Tong. “Women, people of color, and disabled people are also underrepresented as contributors to environmentalism and animal advocacy.”

He remembers how his family often didn’t feel comfortable using green space, and when they did, people often assumed they were tourists. “Before COVID, I was visiting my grandmother and went for a hike in Muir Woods,” north of San Francisco, says Tong. “People asked me where I was from and were surprised to hear I grew up in the Bay Area.” The times when they did feel comfortable, when they enjoyed spending time outdoors, those experiences were memorable and inspired his career path.

Tong hopes to spur more inclusion and representation in the humanities. The STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and math) have benefited from the talents and scholarship of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, he says, but the humanities have not had equal representation. As an Asian American with Hong Kong roots, Tong has often been the sole person of color or Asian American in classes and conferences. Often, he is mistaken as the “tech-person” or assumed to be in a STEM field, he explains.

Tamara Bhalla, an associate professor of American studies and affiliate faculty in the Asian Studies program, works with Tong on the board of the UMBC Asian and Asian American Faculty and Staff Council (AAAFSC). She says, “Chris has been a tremendous leader…He has brought his expansive intellect and global knowledge to bear in his approach to leadership in AAAFSC.”

Part of this work means going beyond the classroom. Tong participated in a series of talks at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco on the theme of “After Hope.” His project helped raise awareness of Chinese-language literature in the context of Asian American history and addressed the pandemic, immigration policies, and what wellbeing means. He includes poetry found on Angel Island in the San Francisco Bay where Chinese immigrants were detained in the early 20th century because of the Chinese Exclusion Act.

“We’re an important part of the conversation on culture, politics, and history in American society,” he says. He wants to be one of the people that students can look to and think, “I can also pursue this path and have a career in academia in a humanistic field.”

Left: At Nanjing University’s main library at the new campus in the Xianlin district. Right: At The No. 2 Historical Archive, the national repository for Republican-era government documents, in Nanjing. Images courtesy of Tong.

Left: At Nanjing University’s main library at the new campus in the Xianlin district. Right: At The No. 2 Historical Archive, the national repository for Republican-era government documents, in Nanjing. Images courtesy of Tong.

Last year’s flood in Zhengzhou was one of many extreme weather events in China that summer. Many cities and villages in various provinces were bombarded by the floods, killing hundreds and displacing millions.

The New York Times reported on the different accounts given by government officials, meteorologists, and on social media, including those trapped in the flooded subway, wading in the water, leaving their homes, and taking care of the dead while also dealing with COVID-19.

In the meantime, Tong has documents that remain to be analyzed in hopes they will unveil more voices and bring further clarity to China’s environmental history and its future.

“The climate crisis affects everyone every where in some way. It’s the most important issue of our generation,” says Tong. “It affects every domain of knowledge production.”

* * * * *

Header Image: A scene from the Yangzi River in China. Photo by Dong Zhang on Unsplash (2017). All other photos shared by Tong.