It’s no secret that at UMBC we do things a little differently. As a university, we’re young, agile, and (buzzword that it may be) truly innovative. We can see the success of these traits in our rankings or research-lab results or employee-satisfaction surveys, but those numbers don’t tell the full story of how, when the Retriever community joins efforts to achieve greatness, we arrive there together.

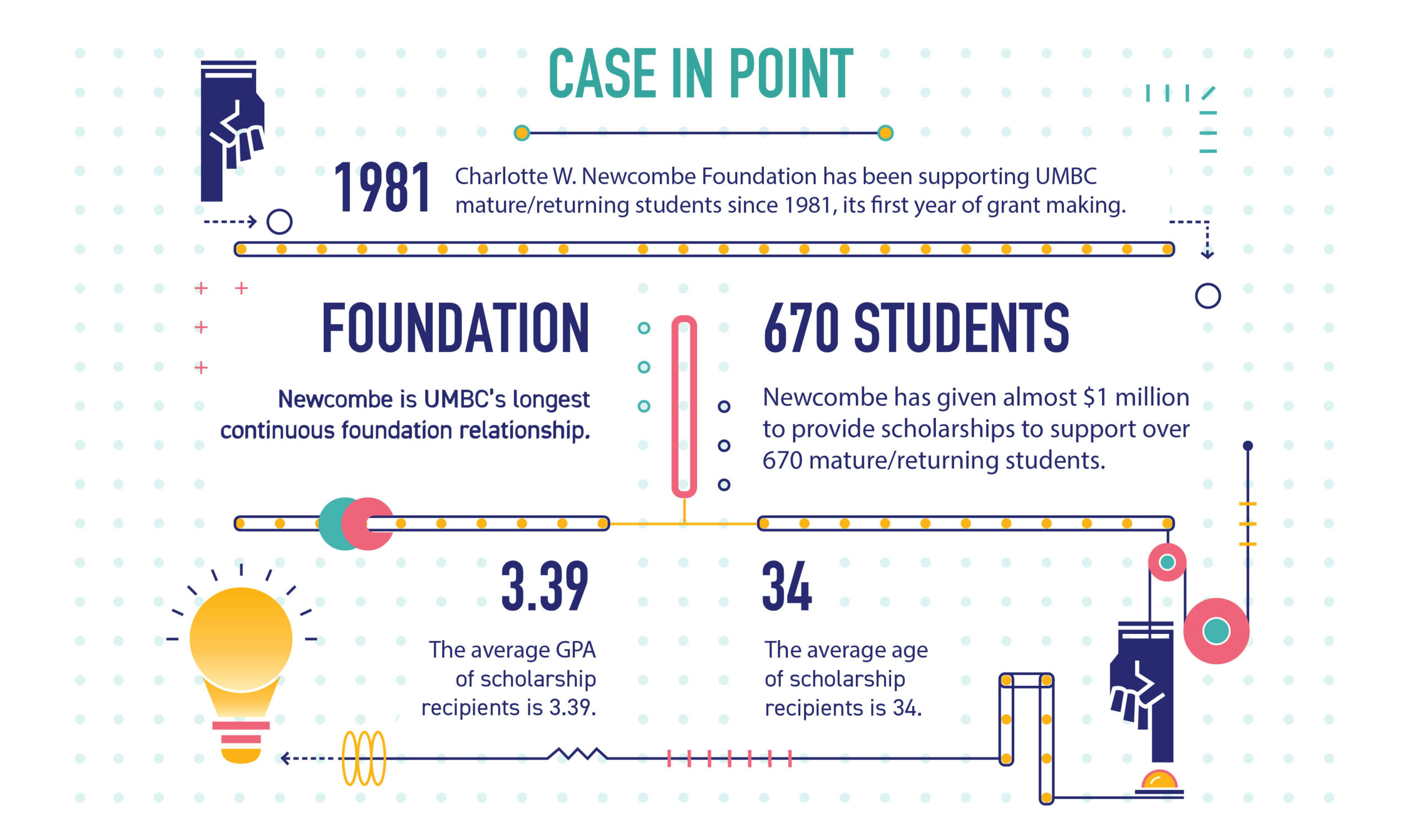

So on the eve of UMBC’s 50th anniversary in 2016, when the institution put forth a goal to raise $150 million— money that goes directly to student scholarships, graduate fellowships, professorial awards, and so much more— we didn’t question if we would succeed, we just wondered how we’d be able to capture the magnitude of the collective campaign when it came to a close.

Now, wrapping up the endeavor with over $189 million, we get to celebrate the stories that made this all possible. This campaign called upon our community’s Grit & Greatness, and Retrievers responded in kind by making big breakthroughs, forging true partnerships, and transforming lives.

Making Big Breakthroughs

The Talent Goes Both Ways

“One of my top priorities is recruiting the best talent who aspire to be great leaders for our company and the nation,” says Jennifer Walsmith, vice president of the Cyber and Information Solutions business unit at Northrop Grumman and executive lead for university relations with UMBC. “Our deep connection with UMBC enables us to recruit and hire the very best. Many of our UMBC graduates have remained at Northrop for decades and play an invaluable leadership role in cybersecurity.”

Walsmith knows something about connection as a Retriever herself, graduating in 1990 with a degree in computer science—something she said was only possible due to 2 a.m. study sessions with classmates and encouraging lunch meet-ups with friends on campus. In her current role, she oversees 2,000 plus employees and is often seen on campus speaking to alumni, faculty, and board members.

“As a nation, we have been enabled by enjoying a technically superior way of life. However, the number of students in the technical fields is getting smaller, especially among women in these majors.” So how do Northrop Grumman and UMBC plan on breaking through that limitation? “I believe it’s vitally important that we all give back,” says Walsmith.

That looks like dozens of UMBC interns each semester who get the chance to work on the toughest problems in space, aeronautics, defense, and cyberspace; an alumni chapter at Northrop Grumman over 600 employees strong who volunteer considerable time at local schools; and millions of dollars spent to benefit students, programs, and research over the last campaign.

Northrop Grumman has a unique relationship with UMBC, but they are not alone in their support of UMBC students and faculty and graduate research. Throughout the Grit & Greatness campaign, 69 percent of commitments came from foundations and companies like T. Rowe Price, Morgan Stanley, Lockheed Martin, and Baltimore Gas and Electric Company.

“We are technical leaders, and I love to see our UMBC students thrive to become future leaders of our company and give back to other students,” says Walsmith. “So when you create the engine where people on each side fuel this relationship, it strengthens everyone.”

— Randianne Leyshon ’09

Breaking Through Education Barriers

In Baltimore City, middle schoolers are making roller coasters out of insulation tubing and tape. High schoolers are dunking basketballs to learn math equations. And not too far away at UMBC, the Sherman STEM Teacher Scholars are prepping to spread even more innovative, inclusive lessons throughout city schools.

The Sherman STEM Teacher Scholars Program, founded in 2006, and other initiatives supporting Retrievers to become culturally responsive and compassionate educators in historically underserved, urban schools, are thanks to the vision of philanthropists Betsy Sherman and her late husband George.

In early 2022, the Sherman Family Foundation donated $21 million to create the Betsy & George Sherman Center, which expands and integrates UMBC’s work in teacher preparation, school partnerships, and applied research focused on early childhood education and improving learning outcomes for Baltimore students. This gift allows educators to implement new teaching methods and find ways to break through learning barriers for their students.

The gift—the largest in UMBC’s history—will transform both UMBC and generations of local students. It also serves as a rallying point for others to join in giving and volunteering at participating schools. To date, says Greg Simmons, M.P.P. ’04, and vice president of Institutional Advancement, “our school partnership work is our most robust community-based philanthropic effort given the scope and range of donors involved.” In addition to the Shermans’ foundational gift, other organizations—like the Richmond Family Foundation and Northop Grumman, just to name two—and many individual donors have supported this endeavor with their own time and resources.

“I see the legacy of the Sherman program as a seed,” says Haleemat Adekoya ’22, political science, a Sherman STEM Teacher Scholar. “It’s been planted and people will continue to water that seed…it will be one of those trees in a folk tale that does not die out because the community and the people who have benefited from its impact see the importance of that tree living beyond generations.”

— Randianne Leyshon ’09

Forging True Partnerships

The Snowball Effect

Sandy Geest ’72, English, knows the power of how a little can go a long way. When she graduated, she immediately started giving to the department that shaped her UMBC experience, “even if it was just 10 or 15 dollars a year,” she says.

Now, 50 years later, Geest and her husband Jay have an endowed scholarship for English majors that has supported 10 students since 2017.

Geest spent most of her career as conference and event planner for James Rouse’s Enterprise Foundation, using her organizational skills to plan ribbon cuttings at the White House and pull together the 1992 U.S. Olympic Gymnastics Trials held in Baltimore. She says it was through the company’s matching shares program that she began to realize the power investments could have—if they could help her savings accrue over time, she wondered how her donations might increase as well.

Geest recounts how her office was located across from the then new Columbia Mall. On lunch breaks, her other coworkers would frequently go shopping. “And I told them, ‘No, you need to be putting your money into this fund because it will grow. When you’re old and gray, you’ll be glad you did that. These shoes will be all worn out by then.’”

Over time, Geest realized the same logic applied to her giving to UMBC. As she got raises and advanced through her career, she upped her giving. “I didn’t do it all at one time, [but] as it grew over the years I gave more and more,” she says, knowing the power for sizable change hinged on an endowment that would be invested by the university and able to sustain its monetary output.

Her scholarship eventually snowballed to support up to four Retrievers a year. Her scholars’ success is the biggest reward, says Geest. At on-campus events, they tell her what a difference her giving made to their UMBC experience—it allowed them to explore career options through internships or it provided a lifeline when they thought they might have to drop out.

“It’s a very good feeling,” says Geest, “to know that you have put a hand back to help somebody behind you.”

— Randianne Leyshon ’09

The Competition Is Strong

Vanessa Mann, head coach for women’s soccer in her fifth season, has the mindset of leaving things better than you found them and uses the competitive spirit inherent in athletics to teach the power of giving back. This philosophy has led to 100 percent participation in UMBC’s annual Black & Gold Rush Giving Day among her student-athletes.

The itch to compete motivates the other teams as well. Women’s lacrosse goalkeeper Isabella Fontana ’24, economics, sees it as the perfect way to get student-athletes engaged. “Not only do I want to support the women’s lacrosse team because everyone loves to support our team,” she says, “but as athletes, we always want to win. So if there’s something on the line, we’re like, ‘Oh, let’s do it.’”

Fontana’s competitive spirit earned her a year-long prime parking spot in front of the Chesapeake Employers Insurance Arena after she won UMBC’s 2022 Giving Day student ambassador challenge. By calling on her enthusiastic network of friends and family, Fontana generated the most donors (104) out of all the ambassadors and brought the lacrosse team’s total to 335, almost double the amount from the previous year. Curious what that looks like by the numbers? It’s the difference between $5,045 in 2020 and a whopping $40,040 in 2022.

The lacrosse team isn’t alone in getting people hyped for giving—in fact, Athletics is responsible for bringing in the most donors and dollars for UMBC’s annual Black & Gold Rush. Even so, they’re always striving to top themselves: in 2020, women’s soccer more than tripled their goal for donors.

Both Fontana and Mann would be the first to remind you that good competition is nothing without cooperation. “So it wasn’t that we were really competing with anyone, like any outside entity,” Mann sums up. “We define competition as competere, which means to strive together. That’s actually the Latin translation. So it’s not me versus you, it’s actually me with you.”

— Levi Lewis ’23

Bridge-Building Alumni

Anwesha Dey came to UMBC from Singapore for a summer research internship. She ended up staying much longer, completing her Ph.D. in biochemistry in 2004. “In many ways, I think of the entire experience being one of the turning points in my life,” says Dey. “The sense of community and belonging and the focus on excellence at UMBC would go on to define my career.”

Now, as director and senior principal scientist of Discovery Oncology at Genentech, a groundbreaking biotechnology company, Dey is dedicated to bringing in UMBC students to her own lab and research community. Early in 2022, that meant inviting her former mentor, Mike Summers, professor of chemistry and biochemistry and the Robert E. Meyerhoff Chair for Excellence in Research and Mentoring, along with then president Freeman Hrabowski to Genentech to discuss the company’s ongoing support of UMBC. “We’re all mutually invested in the same thing,” says Dey. “When we first started this fellowship about five years ago, it was really one step at a time. And so it’s great to see where it is now. The trajectory is really strong.”

Dey is far from alone in bringing her enthusiasm for her alma mater to the workplace, and as more Retrievers go on to work in the upper echelons of the scientific community, they are finding ways to connect their industries to the campus that shaped them.

Bobby Allen ’99, M7, computer science is clear that he has a lot to be thankful for because of UMBC. He met his future wife Frances Allen ’99, M7, computer science, and many of his closest friends as teenagers in the Meyerhoff Program’s Summer Bridge. But aside from his personal connections, as a product manager at Google, it’s Allen’s personal mission to connect UMBC’s proven pipeline of talented Retrievers to his workplace. “At Google, we know we need to have underrepresented populations as managers, champions, executive support, and mentors so that as we hire graduates and interns, they see people who look like them and know what is possible.”

— Randianne Leyshon ’09

Transforming Lives

Rising to the Top

It’s no accident that when visitors arrive on campus from the west entrance, they’re greeted by the radiant reflection on the silver slope of the Performing Arts and Humanities Building (PAHB). This LEED Gold-certified building, which opened in 2014, is a symbol of UMBC’s investment in the performing arts and humanities. But, it’s the students and activities inside the facility that really shine.

Deven Fuller ’23 is a case in point. Double-majoring in dance and math, Fuller is a Linehan Artist Scholar—part of a selective program endowed by Earl and Darielle Linehan that has launched the careers of more than 300 Linehan Artist Scholar alumni in dance, music, theatre, and other creative disciplines.

Fuller is focused on commercial dance—a highly competitive field that’s principally centered in New York and Los Angeles— which would put a career in his chosen field effectively out of reach were it not for the Linehans.

Thanks to the scholarship, Fuller said, he was able to join a New York–based dance training company in his sophomore year, take classes at local studios with accomplished touring commercial dancers, and enjoy other unique opportunities. The fact that the Linehans are “recognizing dance as a serious career…is just such an amazing thing,” Fuller said.

Most recently, with a Linehan Summer Research Award, “I was able to travel and do a certificate program at one of the most prestigious studios in the world for commercial dance. … I was very lucky to have the grant to be able to branch out in that direction.”

Fuller is far from the only student to benefit from philanthropists’ investment in UMBC’s arts-focused students. Todd Carton ’77, interdisciplinary studies, has created the Carton Family Endowed Scholarship to support talented students in the performing arts who come from disadvantaged backgrounds. Along with a gift that helped to fund the PAHB, Carton has included UMBC in his estate plan so that the endowed scholarship can grow and benefit even more arts students far into UMBC’s future.

Fuller hasn’t had the opportunity to meet the Linehans, but if he could, he said, “I would thank them for the opportunities that I’ve been able to have because of them …and let them know how much they are positively affecting the community of artists.”

— Scott Cech

A Family That Gives Together

Professor Bimal Sinha and his family weren’t content to let his 30-plus years of pioneering academic contributions to UMBC be his only professional legacy. Even though neither he nor his sons Jit and Shomo Sinha attended the university, they decided to collectively donate $750,000 to create the Dr. Bimal Sinha Professorship in Statistics at UMBC.

The professorship permanently funds a new statistics faculty position at the university, which seems especially fitting, considering that Sinha founded the statistics department in 1985 and helped transform UMBC into a national leader in statistics education.

But Sinha’s sons remember that beyond his academic accolades, the way their father has always interacted with his mentees is what made the deepest impression— whether meeting international students at the airport or inviting groups of students to their family home for dinner.

Creating community has been a hallmark of Sinha’s career: The professor successfully spearheaded the African International Conference on Statistics, held in a different African country each year since 2014. In 2018, UMBC signed a memorandum of understanding with the University of Limpopo in South Africa to foster collaboration and exchange. A number of graduate students from African countries have also flourished with Sinha’s mentorship.

“Bimal has not only engaged in groundbreaking research for decades but has also produced and championed an impressive number of influential Black statisticians throughout Africa,” noted Freeman Hrabowski, UMBC president emeritus.

In fact, the family’s dedication to continuing Sinha’s legacy has already inspired others: Forty alumni and friends of the university pitched in a combined $150,000, and the Maryland E-Nnovation Initiative Fund committed to a matching grant, bringing the professorship’s total endowment to $1.8 million.

“I feel honored and fortunate to have played a small role in the evolution of this beloved institution,” Sinha said. “Through this gift, I want to ensure that future generations of leading scholars will view UMBC as an attractive home to advance their contributions to the field of statistics.”

— Sarah Hansen, M.S. ’15

Gesture of Gratitude

When Felicia Sanders moved into Susquehanna Hall in the early ’90s as part of the fourth cohort of Meyerhoff Program Scholars, she found herself experiencing a series of firsts. It was her first time living in a mixed-gender dorm; the first time she understood the power of study groups; and she was a member of a scholarship program so new it hadn’t yet graduated its first class of scholars. “I thought I was just making friends, but this setup was really part of an ecosystem, a very effective one that set us up for success.”

The Meyerhoff Scholars Program fosters a collective spirit from day one—when students tackle Summer Bridge together. So when it came time to celebrate the program’s 30th anniversary and thank Robert Meyerhoff, the philanthropist who founded the program with President Emeritus Freeman Hrabowski, the graduates decided to give together, with an initial half-a-million dollar gift.

“When we give collectively, we keep the continuity of the culture that was built by the program,” says Sanders ’96, M4, chemical engineering, and a leadership level giver. “We keep the family bond that was built by the program. It doesn’t become something that is piecemeal or start-stop or becomes intermittent because it is something that was fun for someone one year and then wasn’t supported the following year.”

The word Meyerhoff Scholars most often use to describe themselves is family. Not just a family of 1,300+ alumni who have gone on to use their gifts as industry leaders and academic powerhouses, but including the students who have yet to join their ranks as scholars, the future generation of Meyerhoffs.

Jason Dixon ’02, M10, computer science, and Rhea Brooking-Dixon ’02, M10, biological sciences, whose origin story began in Summer Bridge, give together because “we know that our successes are never truly our own,” they share. “We are confident that our gifts to UMBC and the Meyerhoff Scholars Program will help other young scholars the same way the program has helped us and more.”

“It’s important for the family to be engaged in the program’s continuity,” says Sanders. “Now that Doc [Hrabowski] has moved on to the next chapter of his life, it’s important that the Meyerhoff Program is something we’re still talking about in another 30 years. And that can’t happen if the family doesn’t continue to reinvest.”

— Randianne Leyshon ’09